Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

French common name: Panais sauvage

Order: Apiales

Family: Apiaceae

Did you know? The leaflets of wild parsnip are toothed and often shaped like a mitten.

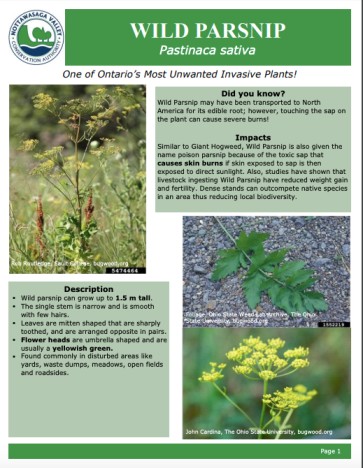

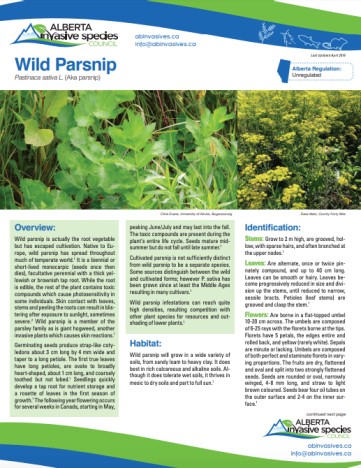

Wild parsnip is a member of the carrot/parsley family, and like giant hogweed, produces sap containing chemicals that can irritate human skin. In North America, scattered wild parsnip populations are found from BC to California, and from Ontario to Florida, while being reported in all provinces and territories of Canada expect Nunavut. The plant forms dense stands that outcompete native plants, reducing biodiversity and the quality of agricultural forage crops such as hay, oats, and alfalfa. Wild parsnip can grow up to 1.5 m tall with compound leaves arranged in pairs, with sharply-toothed leaflets that are shaped like a mitten. Small clusters can be removed with proper protective clothing.

Parsnip is a plant that is familiar to many of us in its culinary form. It has been grown as a root crop for centuries. The first reports of a cultivated form in Canada are from the early 1600s and “wild” populations were noted around European settlements. The entire plant has a distinct “parsnip” odour. While wild parsnip is not as widely grown as an agricultural crop as it once was, it’s still a staple in many of our kitchens. It is the wild variety of this plant that is causing concern and spreading along roadsides, agricultural fields, railroad embankments, and other disturbed habitats. As populations expand, more people come into contact with the plant, its invasive qualities, and the toxic compounds that can cause serious burn-like rashes.

Height: Wild parsnip can grow to a height of 0.5-1.5 m.

Stems: Wild parsnip has a single light green (sometimes purple-tinged), deeply-grooved, hollow stem (except at the nodes) and stands between 0.5-1 m tall. The stem is smooth (with few hairs) and typically 2.5-5 cm in diameter.

Leaves: The leaves of wild parsnip are alternate on the stem, pinnately compound, approximately 15 cm in length, with saw-toothed edges. Leaves are further divided into leaflets that grow across from each other along the stem, with 2-5 pairs of opposite leaflets and one diamond-shaped terminal leaflet. The petiole (the stem of the leaf) on lower leaves is longer than that on leaves closer to the top of the stem.

Roots: Wild parsnip has a thick funnel-shaped taproot, which can grow to a depth of 1.5 m. This root is where energy reserves are stored during its first year. It is thought to benefit the plant during times of drought, storing moisture and nutrients.

Flowers: Wild parsnip has small 5-petalled flowers growing in clusters that, in Canada, bloom from June through to October. Petals are yellow, usually without bracts or bractlets (small leaves at the base of the flower), with small or non-existent sepals (small leaves that protect flowers before they open). Flowers are arranged in 15-25 rays of unequal length and grow in a flat, umbrella-shaped umbel that is 5-15 cm across.

Fruit: After flowering, wild parsnip plants produce a dry fruit or seed called a schizocarp. This fruit is about 6 mm long and oval. Once matured, the schizocarp splits into two sections called mericarps, which are flat, smooth, round and 5-7 mm long. Each mericarp contains a seed, which matures in mid-summer. Seeds usually remain attached to the dead stalks and seed dispersal can take place between August and November (with September being the most common time). Seeds can remain viable in soil for up to 5 years.

Wild parsnip is native to much of temperate Europe, eastern Europe, and western/central Asia (growing in Turkey, Iran, the Caucasus region, and the Western Himalayans). During the last 15-20 years, wild parsnip has become increasingly common around eastern Ontario, with large populations east of Belleville and in western Quebec. It is now spreading west across the province. In the United States, wild parsnip is found in most states, with the exception of Alabama, Hawaii, Georgia, and Florida.

Impacts to biodiversity

Wild parsnip invades disturbed areas such as roadsides, pastures, crop land, and fields with reduced tillage use. It outcompetes native vegetation, particularly crowding out lower-growing plants. It can also have an impact on pollinators, as honeybees do not visit the plant and it may displace other, more pollinator-friendly plants such as goldenrod (Solidago spp.).

Impacts to agriculture

Wild parsnip can reduce the quality of some agricultural forage crops. In agricultural operations using a no-till or reduced tillage system, it is a concern, as perennial weeds such as wild parsnip are able to take over. Wild parsnip is not valuable as a forage plant; the chemical compounds in wild parsnip inhibit weight gain and fertility in livestock that feed on it.

Impacts to human health

Both the wild and cultivated forms of parsnip contain toxic compounds, called furanocoumarins. These compounds can cause serious rashes, burns, or blisters to skin exposed to the sap and then sunlight. The plant poses a risk to agricultural workers, those involved with vegetation control, and to people unknowingly exposed to the plant in the wild. The roots of wild parsnip (non-cultivated form) may also contain furanocoumarins. Therefore, it is recommended that the root of this plant not be consumed.

Learn how to identify wild parsnip and avoid accidentally spreading it through recreation and gardening.

- Stay on trails and away from areas known to have wild parsnip or other invasive species.

- Inspect, clean, and remove mud, seeds, and plant parts from clothing, pets (including horses), vehicles (including bicycles,) and equipment such as mowers and tools.

- Before travelling to new areas, clean vehicles and equipment in a place where plant seeds or parts aren’t likely to spread, such as in a driveway or at a car wash. It’s very important to carefully wash any sap from clothing, equipment, and pets.

- Avoid disturbing soil and removing plants from natural areas; they may be rare native plants or even invasive plants.

Technical Bulletin

In 2017, the Early Detection & Rapid Response Network worked with leading invasive plant control professionals across Ontario to create a series of technical bulletins to help supplement the Ontario Invasive Plant Council’s Best Management Practices series. These brief documents were created to help invasive plant management professionals use the most effective control practices in their effort to control invasive plants in Ontario.

*Please note: the Invasive Plant Technical Bulletin Series is currently undergoing some updates and will be reposted when the process has been completed. Please visit the Ontario Invasive Plant Council website for updates.

Fact Sheets

Best Management Practices

These Best Management Practices (BMPs) are designed to provide guidance for managing invasive Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum) in Ontario. They were developed by the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC), its partners and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNRF) and Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). These guidelines were created to complement the invasive plant control initiatives of organizations and individuals concerned with the protection of biodiversity, agricultural lands, crops and natural lands

Research

Generalist and specialist host–parasitoid associations respond differently to wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) defensive chemistry

herbivores and their parasitoids than on specialist herbivores and their parasitoids. 2. This

prediction was examined by comparing the effects of the wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa L.) …

Patterns of Genetic Diversity in the Globally Invasive Species Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

are native to Eurasia and have been cultivated for more than five centuries. It is unclear

whether the global invasion of this species is a consequence of escape from cultivation or …

Current Research and Knowledge Gaps

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Further Reading

The Invasive Species Centre aims to connect stakeholders. The following information below link to resources that have been created by external organizations.