Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae)

Hemlock woolly adelgid looks like white, woolly masses at the base of hemlock needles.

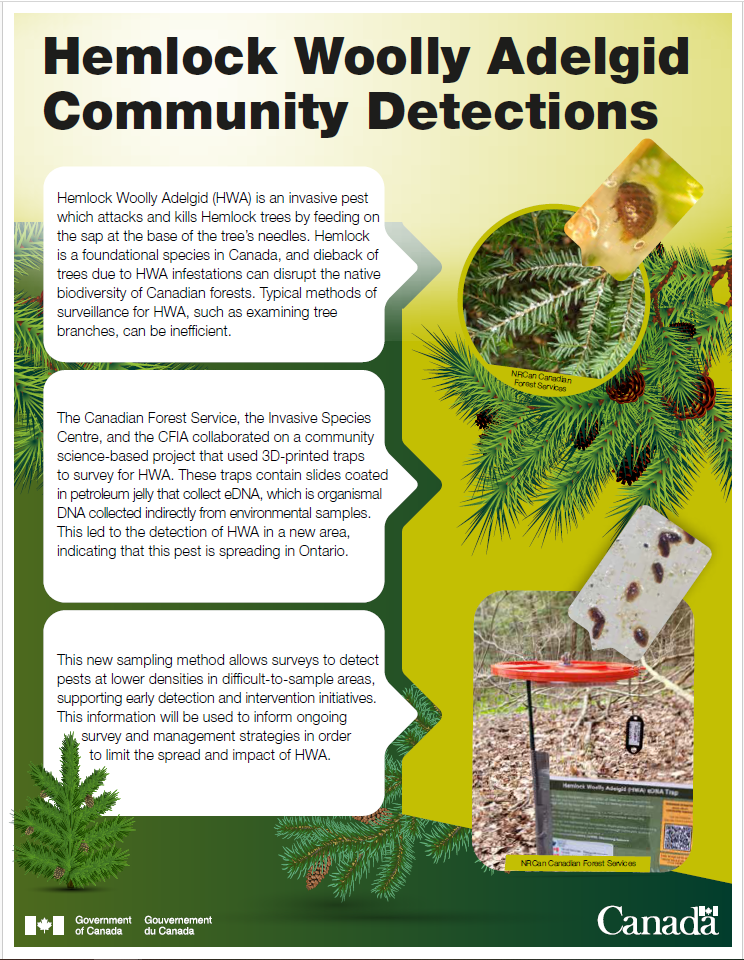

Hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) has recently been detected in Port Colborne, Ontario.

Detections as of April 2024:

- Niagara Falls, Ontario: 2013, 2015, 2019

- Southwestern Nova Scotia: 2017

- Wainfleet, Ontario: 2019

- Fort Erie, Ontario: 2021

- Pelham, Ontario: 2022

- Grafton, Ontario: 2022

- Hamilton, Ontario: 2023

- Halifax County, Nova Scotia: 2023

- Haldimand County, Ontario: 2023

- Hants County, Nova Scotia: 2023

- Lincoln, Ontario: 2023

- Port Colborne, Ontario: 2024

You can learn more about detections here.

New Resource!

Guide for Managing Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae)

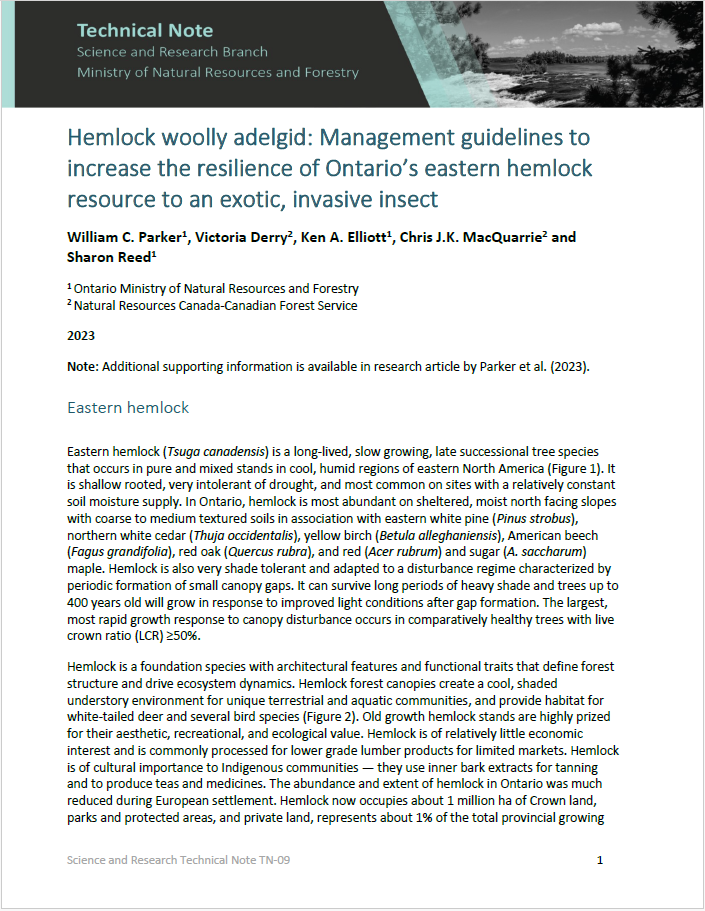

This guide presents the most up-to-date information available to inform management decisions for hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) in Ontario. The guide will be updated based on insect monitoring results, research advances, and program development. If you notice a gap in topics covered or find an error, please

contact the Invasive Species Centre (ISC) at info@invasivespeciescentre.ca. If you have implemented a management strategy to prevent or control HWA and have results to share, please reach out to the ISC at the email listed above.

Order: Hemiptera

Family: Adelgidae

Hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) is an aphid-like insect (aphids suck fluid from plants) that attacks and kills hemlock trees by feeding on nutrient and water storage cells at the base of needles. Researchers believe HWA was first brought to the United States via infested nursery stock from Japan. The pest was first discovered near Richmond, Virginia in the 1950s and has since established along the eastern coast of the United States with sightings reported from Maine to Georgia.

In Canada, eastern provinces are at-risk due to proximity to HWA populations in the states. In 2017, HWA was found and is now being closely monitored in the southwestern Nova Scotia counties of Digby, Queens, Shelburne, Yarmouth, Annapolis, and most recently, Lunenburg in 2020.

HWA was initially detected and subsequently eradicated in Etobicoke in 2012 and Niagara Falls, Ontario in 2013. In 2019 HWA was confirmed in two small populations near Wainfleet and Niagara Falls, Ontario. In October 2021, HWA was also confirmed in Fort Erie, Ontario. HWA is federally regulated by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), which continues to monitor current populations.

In British Columbia, a genetically different strain of HWA causes minor damage to western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) trees, which are protected by natural resistance to HWA and natural predators that control HWA.

Jump to:

Did you know?

Hemlock woolly adelgid has two different generations and three forms within one year!

Life Cycle

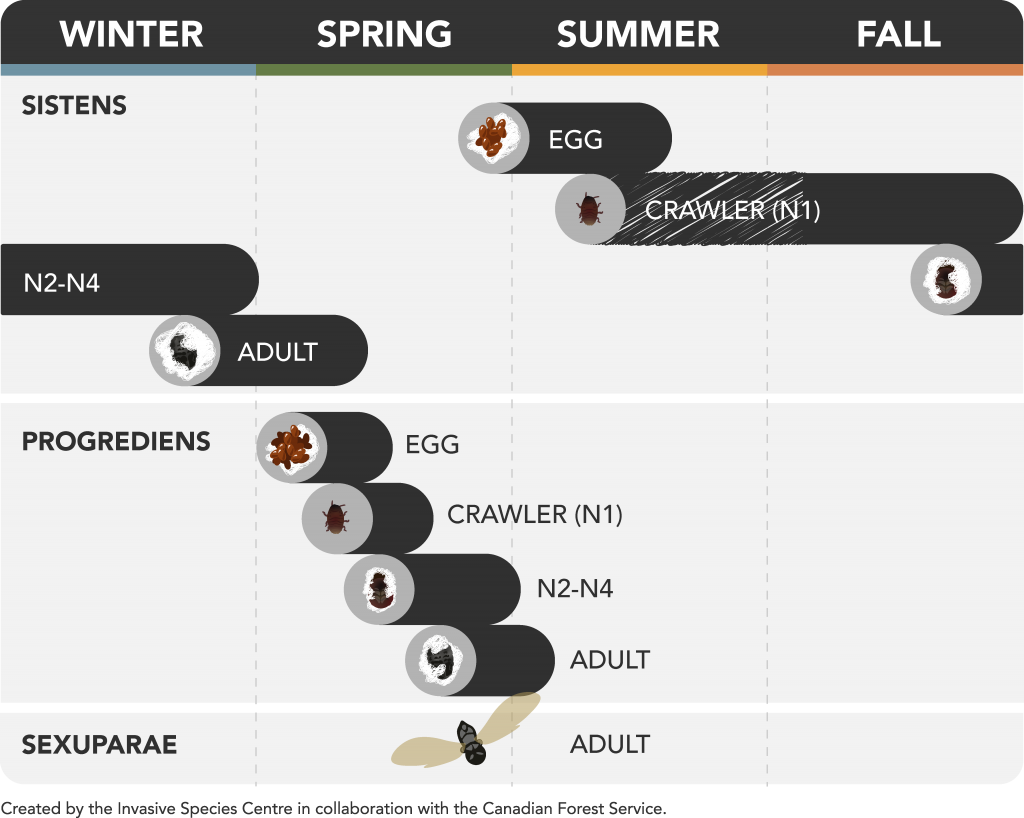

There are two generations and three forms of hemlock woolly adelgid in North America. The two generations that occur on hemlock are known as sistens and progrediens (plural sistentes and progredientes), all of which are female and reproduce asexually. The second generation of HWA can produce two forms: progrediens adults (which are wingless and stay on hemlock) or sexuparae (which have wings and migrate to spruce). Sexuparae are not known to survive on native North American spruces or on spruce trees from their native range that have been transplanted in North America. As the sexuparae form is not important to the biology of HWA in North America, we focus on the sistens and progrediens forms that attack hemlock.

The sistens generation, sometimes referred to as the overwintering generation, is present from June until March of the following year; whereas the progrediens generation (spring generation) is present from March until June (Fidgen and Turgeon, 2016). Both generations have six stages of development: eggs, four nymphal instars, and adults (Cheah et al., 2004). Once progrediens adults oviposit (lay eggs) on hemlock, the sistens generation hatches in June-July. The newly hatched first instar nymph is known as a crawler, which becomes inactive for the remainder of the summer shortly after hatching (called aestivation; CFIA, 2019). In mid-October, the crawler will resume feeding and continue to develop through the four nymphal instar stages. Following this, the sistens generation matures into full adults in early May. These adult sistentes each produce a single ovisac containing up to 300 eggs, which hatch to produce progredientes. Because there is no diapause or overwintering requirement for the progrediens generation, the life cycle occurs rapidly, usually from spring to early summer.

Physical Description

| Life stage | Sistentes (First generation) | Progredientes (Second generation) | Sexuparae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs (oblong and amber) | Eggs laid by progrediens adults are 0.36 mm long by 0.23 mm wide. Eggs are laid in a batch of 25-125 with a spherical “woolly” ovisac (egg covering) made of white, waxy threads. | Eggs laid by sistentes are 0.35 mm long by 0.21 mm wide. These eggs are laid in a larger batch of 50-175 eggs (up to 300) with a larger woolly ovisac. | Sexuparae develop from second generation eggs. Adult sexuparae deposit up to 15 eggs, 0.37 mm long by 0.25 mm wide, beneath their wings. However, the nymphs that emerge from these eggs do not develop any further. |

| Crawlers (first instars) | Brown-orange in colour and 0.44 mm long by 0.27 mm wide. | Same as sistentes. | Same as sistentes and progredientes. |

| Second instars | Have short, thick legs and are 0.57 mm long by 0.34 mm wide. | Same as sistentes. | 0.60 mm long by 0.35 mm wide. |

| Third instars | 0.67 mm long by 0.43 mm wide. | Same as sistentes. | 0.77 mm long by 0.47 mm wide. |

| Fourth instars | 0.74 mm long by 0.47 mm wide. | Same as sistentes. | 0.89 mm long by 0.49 mm wide. |

| Adults | Adult sistentes are about 1.41 mm long by 1.05 mm wide and are engulfed by a heavy waxy coating. | Adult progredientes also have a waxy coat and are about 0.87 mm long by 0.63 mm wide. | Adult sexuparae are about 1.09 mm long and 0.51 mm wide. They are dark brown and have long antennae (five-segmented), compound eyes, and four textured wings. |

Table information from CFIA HWA species fact sheet.

Left photo: HWA eggs are oblong and amber and surrounded by a spherical “woolly” ovisac. Photo: Shimat Joseph, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org.

Right photo: HWA adults are small, brown insects. Photo: Michael Montgomery, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Left image: Eastern hemlock. Photo: Jack Pearce, Flickr.

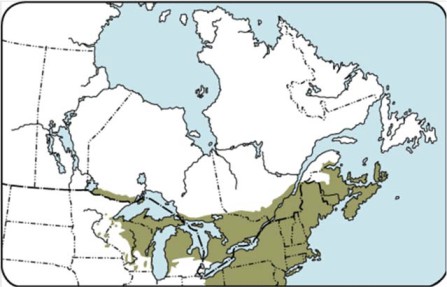

Right image: Eastern hemlock distribution in eastern Canada and northern states. Source: https://tidcf.nrcan.gc.ca/en/trees/factsheet/75 via Emilson et al., 2018.

The primary tree species at risk from HWA in Canada is eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Eastern hemlock is located throughout the Maritime provinces, southern Quebec, southern Ontario, and northwestern Ontario (see map).

Other species that have been attacked by HWA include (CFIA, 2019):

- Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana)

- Chinese hemlock (Tsuga chinensis)

- Japanese hemlock (Tsuga diversifolia)

- Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla)

- Mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana)

- Southern Japanese hemlock (Tsuga sieboldii)

- Himalayan hemlock (Tsuga dumosa)

- Yeddo spruce (Picea jezoensis hondoensis)

- Tiger-tail spruce (Picea polita)

Signs of infestation by HWA include (Havill et al., 2014):

- White “woolly” sacs at the base of hemlock needles on most recent twigs

- Premature bud and shoot dieback

- Premature needle loss

- Thinner, greyish-green crown

- Dieback of twigs and branches

- Discolouration of foliage

- Death within 4-15 years

Left: Early HWA infestation, showing “woolly” egg sacs. Photo: Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

Right: Late HWA infestation. Photo: Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org

HWA damage. Photo: William M. Ciesla, Forest Health Management International, Bugwood.org

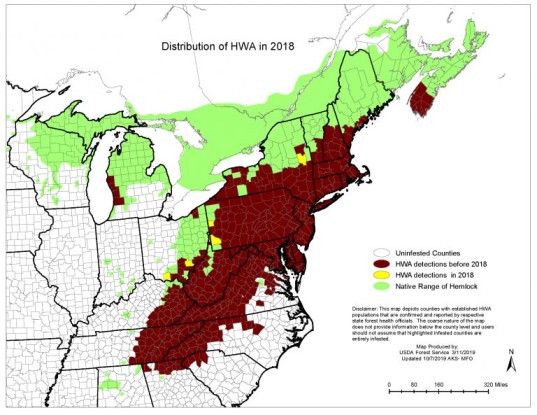

HWA is native to Asia and was likely first introduced to Richmond, Virginia in 1951 on infested planting stock. HWA can now be found in every state from Georgia northeast to Maine – and six of those states share a border with eastern Canada (see photo below).

Photo: HWA and hemlock distribution in the United States and southeastern Canada. (Source: USDA Forest Service/AKS-MFO via Maine Forest Service)

Ontario

HWA was found and subsequently eradicated in Etobicoke, Ontario in 2012 and Niagara Falls, Ontario in 2013.

As of October 2023, the affected areas in Ontario include Niagara Gorge, Fort Erie, Wainfleet, Pelham, Hamilton, Grafton, Haldimand County, and Lincoln

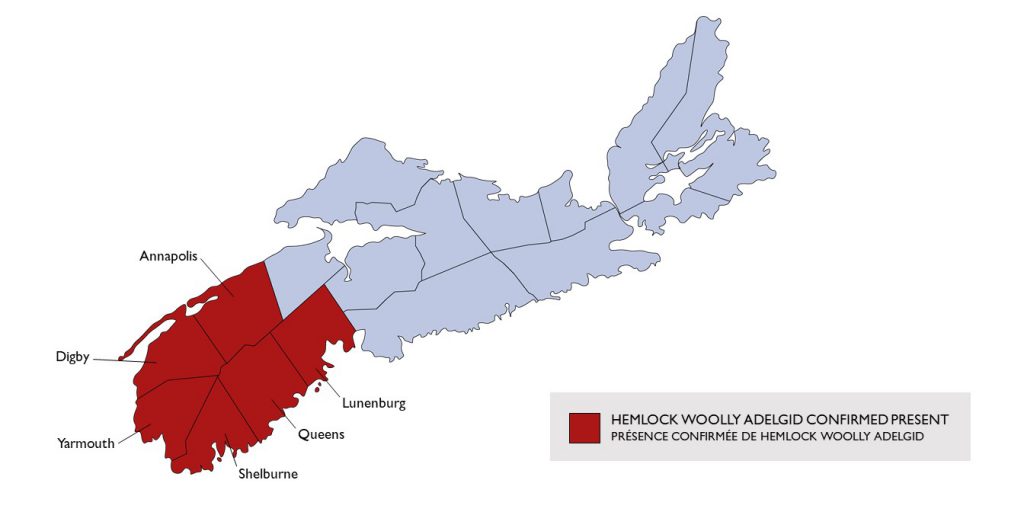

Nova Scotia

In 2017, HWA was detected in southwestern Nova Scotia. It has since spread and is being monitored in the Nova Scotia counties of Digby, Queens, Shelburne, Yarmouth, Annapolis and most recently, Lunenburg. Survey activities for this pest are ongoing to determine the extent of its spread and to foster early detection in other areas.

Photo: HWA distribution in Nova Scotia.

British Columbia

A non-invasive, genetically distinct strain of HWA can be found throughout the Pacific northwest of the United States and Canada, where its population is thought to be controlled by a combination of natural enemies and host resistance.

HWA can survive in plant hardiness zones 5a and higher (Kanoti et al., 2015), which puts most of Canada’s hemlock trees at risk. Furthermore, experts believe that cold tolerance is an adaptive trait, meaning that HWA could evolve to tolerate colder climates as it spreads northward into Canada. Dispersal of HWA occurs by wind, animals, and human movement of nursery stock, logs, and other wood products (CFIA, 2018). Spread rates have been estimated at up to 20-30 km per year (Ontario HWA Working Group, 2014).

There are import and domestic movement requirements for all hemlock (Tsuga spp.), yeddo spruce (Picea jezoensis), tiger-tail spruce (Picea polita), and many of these species’ tree products to prevent the introduction and spread of HWA (CFIA, 2018).

The following CFIA policy relates to HWA:

- D-07-05 – Phytosanitary requirements to prevent the introduction and spread of the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) from the United States and within Canada (this page is under review)

- Notice to industry – New movement restrictions in place to prevent the spread of hemlock woolly adelgid [May 28, 2020]

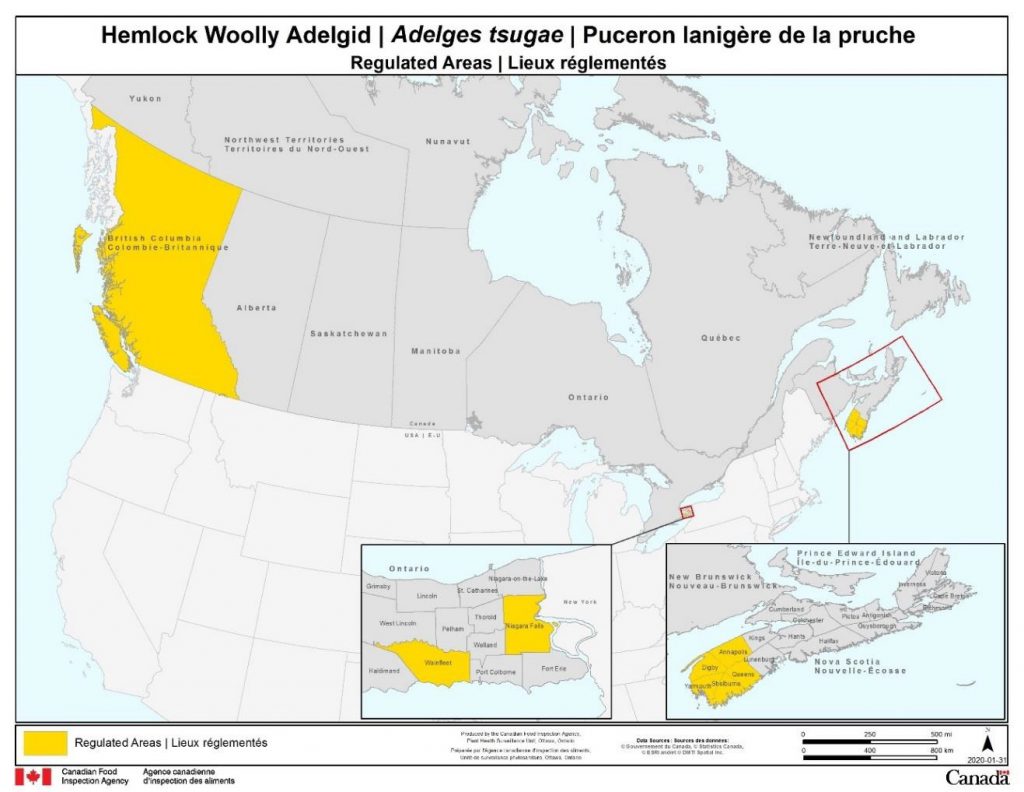

Effective December 15, 2017, an Infested Place Order under the Plant Protection Act was declared for the counties of Digby, Queens, Shelburne, Yarmouth, and Annapolis in Nova Scotia and the entire province of British Columbia. In 2020, movement restrictions and regulated materials were added for the City of Niagara Falls and township of Wainfleet in Ontario.

Check the CFIA HWA profile for updates on the most recent regulations.

Photo: Areas in Canada regulated for HWA. (Source: CFIA)

Ecological Impacts

Several animal species require hemlock forest for part, or all, of the year (Chowdhury, 2002). Many birds use hemlock trees as a food source and for nesting and roosting sites. Hemlock trees are also commonly found in riparian areas, where they play an important role in regulating and maintaining water temperatures. For example, the canopies of hemlock trees can shade streams, cooling the water and making it habitable for brook trout. In winter, hemlock provides a valuable thermal cover to deer and birds during cold weather. Along riverbeds, hemlock also plays an important role in streambank stabilization, especially in steep gorges.

HWA can cause significant changes to hemlock ecosystems, impacting both living communities of flora and fauna and ecosystem services. Loss of eastern hemlock could result in changes in energy inputs, nitrogen cycling, microclimate environment, and physical environment, all of which could negatively affect the health of vegetation, birds, aquatic organisms, and mammals (Snyder et al., 1998).

The loss of hemlock trees also makes forests vulnerable to invasive species that thrive in disturbed areas, like dog-strangling vine or garlic mustard.

Photo: Hemlocks along a stream. (Source: Gabriel Popkin)

Social Impacts

Hemlock trees are popular ornamental trees and would be a significant aesthetic loss. In residential areas, hemlock trees provide shade and thermal protection, and their death would result in negative impacts to property values (Li et al., 2014). HWA infestations can also affect recreation experiences. Loss of hemlock trees can affect stream temperatures, and in turn, affect fishing quality. The defoliation and loss of trees could also affect the quality of recreational hiking activities.

Economic Impacts

The economic value of hemlock to the forest industry is not as high as other trees species, however, eastern hemlock can be processed for use in general construction or as pulp (CFIA, 2018).

Photo: Hemlock siding. (Source: River Valley Woodworks)

Prevent

All Canadians can play a role in preventing the spread of HWA. Important preventative actions include:

- Avoid placing bird feeders near hemlock trees – birds can accidentally transport HWA to new locations.

- Don’t move firewood! Human movement of wood products increases the spread of HWA.

- In the spring, keep an eye out for signs, such as woolly egg masses, on your hemlock tree and report any potential sightings.

Detect

Since HWA is passively spread by wind, birds, animals, and humans, this pest can move long distances and poses a significant threat of establishment in provinces adjacent to infested eastern states. Visual surveys to detect HWA are conducted annually in Canada at high risk sites. These sites include current and historic importers of hemlock nursery stock and areas at risk of natural spread, including green spaces/urban parks and hemlock forest stands within 100 km of the Canada/United States border (Ontario HWA Working Group, 2014).

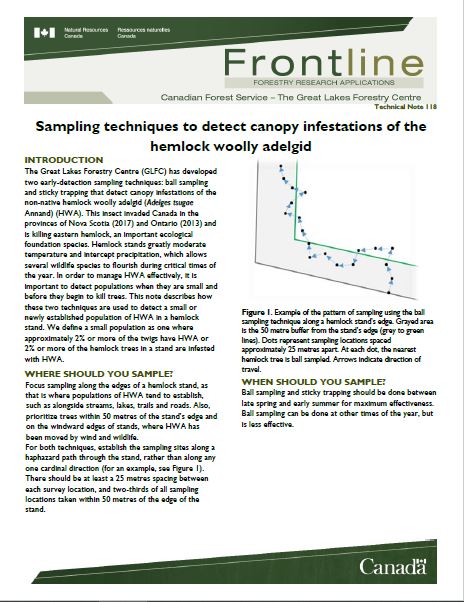

Visual surveys are only able to examine a small portion (within 6 m of ground level) of potential HWA habitat, whereas hemlock crowns can reach heights of 30 m or more (Farrar, 1995). Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service researchers are attempting to improve the reach of ground-based detection surveys with two new sampling methods: ball sampling and sticky trap sampling. Ball sampling involves launching VELCRO®-covered racquetballs into the crown with a slingshot to check for HWA wool, while sticky trap sampling intercepts first instar crawlers as they fall from the crown (Fidgen, Whitmore, and Turgeon, 2015). To learn more about these techniques, click here.

HOW TO: Sticky Trap Sampling for HWA

Photo: Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service researcher Chris MacQuarrie using the ball sampling method.

If you think you’ve seen HWA, report your sighting! You can report Canada-wide sightings to cfia.surveillance-surveillance.acia@canada.ca or to eddmaps.org in Ontario.

You can also download and complete the following sampling protocol:

- Survey Guidelines for Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) – ENGLISH

- Lignes directrices pour les enquêtes sur le puceron lanigère de la pruche (Adelges tsugae Annand) – FRANÇAIS

When conducting surveys in accordance with this protocol, please contact the CFIA so all partner activities can be tracked as part of the national surveillance efforts.

Respond and Control

Mechanical control

In Canada, mechanical control may be used to manage HWA. Infested trees are cut down and burned onsite. Delimitation surveys are used to monitor the success of the eradication treatment (Ontario HWA Working Group, 2014).

Chemical control

Insecticide formulations with the active ingredients imidacloprid or dinotefuran are widely used in the United States. Methods of applying these active ingredients include soil applied treatments (e.g. time-released tablets or drenches), basal bark sprays, and tree injection (see photo below). Initial studies suggest that a tank mix of imidacloprid and dinotefuran applied as a basal bark spray may be the most optimal chemical control tactic (Invasive Species Centre, 2015).

Photo: Soil drenching with imidicloprid. (Source: Great Smoky Mountains National Park Resource Management, USDI National Park Service, Bugwood.org)

Biological control

It is generally agreed that the best strategy to achieve long term protection of hemlock over the landscape is with biological control agents of HWA. Researchers in the United States and Canada are currently investigating the rearing and release of several predators of HWA from parts of the world where HWA is native or naturalized (e.g. the Pacific Northwest, China, Japan). Before being released into a new habitat, the prospective biological control agents undergo rigorous laboratory testing in quarantine to make sure their environmental impact is restricted to the targeted prey – in this case, HWA.

The tooth-necked fungus beetle (Laricobius nigrinus) and two silver flies (Leucopis piniperda, Leucopis argenticollis) native to the northwest United States and British Columbia are voracious predators of the adelgid and are being actively released across the eastern USA. Several other predators, mostly from the far east, are in various stages of quarantine evaluation, release, and monitoring of their efficacy in the wild (Invasive Species Centre, 2015). In addition to these insects, at least two fungal pathogens as biological control agents of HWA seem effective (Havill, Vieira, and Salom, 2014).

Photo: Tooth-necked fungus beetle adult. (Source: Ashley Lamb, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Bugwood.org)

Photos: Biological control release in New York state.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). (2018). D-07-05: Phytosanitary requirements to prevent the introduction and spread of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) from the United States and within Canada. http://www.inspection.gc.ca/plants/plant-pests-invasive-species/directives/forestry/d-07-05/eng/1323754212918/1323754664992.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). (2019). Adelges tsugae (Hemlock Woolly Adelgid) – Fact Sheet. https://www.inspection.gc.ca/plant-health/plant-pests-invasive-species/insects/hemlock-woolly-adelgid/fact-sheet/eng/1325616708296/1325618964954.

Cheah, C., Montgomery, M. E., Salom, S., Parker, B. L., Costa, S., & Skinner, M. (2004). Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2004-04. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Carole_Cheah/publication/235323687_Biological_control_of_hemlock_woolly_adelgid/links/54217b650cf203f155c6d740.pdf.

Chowdhury, S. (2002). Introduced Species Summary Project – Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Adelges tsugae). http://www.columbia.edu/itc/cerc/danoff-burg/invasion_bio/inv_spp_summ/Adelges_tsugae.html.

Costa, S. & Onken, B. (2006). Standarized Sampling for Detection and Monitoring of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid in Eastern Hemlock Forests. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2006-16. https://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/HWASampling.pdf.

Emilson, C., Bullas-Appleton, E., McPhee, D., Ryan, K., Stastny, M., Whitmore, M., & MacQuarrie, C. (2018). Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Management Plan for Canada, Natural Resources Canada. http://invasiveinsects.ca/hwa/HWA%20management%20plan%20Canada.pdf.

Farrar, J. L. (1995). Trees in Canada, Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Headquarters. Fitzhenry and Whiteside Limited.

Fidgen, J. G. & Turgeon, J. J. (2016). Detection tools for an invasive adelgid. Frontline Technical Note No. 116. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/rncan-nrcan/Fo123-1-116-eng.pdf.

Fidgen, J. G., Whitmore, M. C., & Turgeon, J. J. (2015). Ball sampling, a novel method to detect Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) in hemlock (Pinaceae). The Canadian Entomologist, 00(2015), 1-4. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jean_Turgeon3/publication/277978116_Ball_sampling_a_novel_method_to_detect_Adelges_tsugae_Hemiptera_Adelgidae_in_hemlock_Pinaceae/links/55d739d208ae9d65948d85b6.pdf.

Havill, N. P., Vieira, L. C., & Salom, S. M. (2014). Biology and Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2014-05 Revised June 2016. http://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/HWA-FHTET-2014-05.pdf.

Invasive Species Centre. (2015, May 1). Hemlock Woolly Adelgid – A formidable pest we CAN manage: Dr. Mark Whitmore [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1q0wqno4N20.

Kanoti, A., Lombard, K., Weirmer, J., Schultz, B., Esden, J., Hanavan, R., & Bohne, M. (2015). Managing Hemlock in Northern New England Forests Threatened by Hemlock Woolly Adelgid and Elongate Hemlock Scale. United States Department of Agriculture. https://extension.unh.edu/resources/files/Resource005573_Rep7772.pdf.

Li, X, Preisser, E. L., Boyle, K. J., Holmes, T. P., Liebhold, A., & Orwig, D. (2014). Potential Social and Economic Impacts of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid in Southern New England. Southeastern Naturalist, 13(6), 130-146.

McClure, M. S., Salom, S. M., & Shields, K. S. (2001). Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2001-03. http://na.fs.fed.us/fhp/hwa/pubs/proceedings/2001/fhtet-2001-03.pdf.

Ontario HWA Working Group. (2014, June 20). Hemlock woolly adelgid in Ontario [Video Webinar]. Adobe Connect. https://silvecon.adobeconnect.com/p6hn324kfd5/?launcher=false&fcsContent=true&pbMode=normal.

Reardon, R., Onken, B., Cheah, C., Montgomery, M. E., Salom, S., Parker, B. L., Costa, S., & Skinner, M. (2004). Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. USDA Forest Service Publication FHTET-2004-04. http://wiki.bugwood.org/Archive:HWA/Introduction.

Snyder, C., Young, J., Smith, Lemarie, D., Ross, R., & Bennett, R. (1998). Influence of eastern hemlock decline on aquatic biodiversity of Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Monitoring Network

The Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA) Monitoring Network was initiated to increase early detection of HWA outside of known distribution and regulated areas. This program is coordinated by Invasive Species Centre, in partnership with Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA).

The HWA Monitoring Network will be an invaluable source of information on the spread and distribution of hemlock woolly adelgid. The program offers a unique opportunity for community members to become actively involved in monitoring and stewardship of their woodlots.

Learn more here.

Fact Sheets

Management Resources

Research

Sticky traps as an early detection tool for crawlers of Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae)

populations of first-instar nymphs of the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand), a

pest of hemlocks (Tsuga spp.[Pinaceae]) in North America. We considered the detection rate …

(Tsuga (Endlicher) Carrière; Pinaceae) in the eastern United States of America and was

discovered recently in Nova Scotia, Canada. We evaluated the use of a Velcro-covered …

A decision framework for hemlock woolly adelgid management: Review of the most suitable strategies and tactics for eastern Canada

the eastern United States, and presents a significant threat to all eastern hemlock in Canada

across Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, especially

since the recent detection of its widespread establishment in southwest Nova Scotia. The

spread and rising infestation level and impacts of HWA in this region serve as a warning for

forest managers across eastern Canada to develop appropriate management plans and …

Assessing an integrated biological and chemical control strategy for managing hemlock woolly adelgid in southern Appalachian forests

woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae Annand (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) is considered an invasive

pest of eastern hemlocks; an ecologically foundational tree species …

Mortality and recovery of hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae) in response to winter temperatures and predictions for the future

Maine … Hemlock woolly adelgids found only on new growth were examined from the branches

within 48 h … Hemlock woolly adelgid viability was assessed with a dissecting microscope …

Further Reading

The Invasive Species Centre aims to connect stakeholders. The following information below link to resources that have been created by external organizations.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency – Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Fact Sheet