July 26, 2024

Countless poems have been written about nature’s splendor – bird song, wildflowers, and the changing of the seasons come to mind. Invasive species would seem to be less desirable subjects for the musings of a poet, yet twenty-one of them feature in Amelia Gorman’s poetry collection Field Guide to Invasive Species of Minnesota.

A writer of weird fiction, Gorman challenges us to think about how invasive species might shape our future, including in surreal and fantastical ways. Field Guide is simultaneously a caution against monoculture and a tribute to the strange and resilient plants and animals that remind us of home (in this case, the state where Gorman lived for fifteen years), whether we want them there or not. The Invasive Species Centre interviewed Gorman about her creative approach, ecological grief, and of course, her favourite field guides. Read her responses below.

Interview with Amelia Gorman

1. In your poetry chapbook’s Author’s Note, you assert the importance of writing about “a climate change and ecological damage we will have to live with, not one foisted off ‘til next century.” Does your poetry help you to grapple with ecological grief? Do you think this is part of what makes it appealing to readers?

Oh gosh, I don’t know. It almost feels a little weird, like soothing ourselves over this self-created problem. I would describe it more of a call to action, or maybe a sort of step necessary before a more recent call to action. That is, asking people to really start seeing on a more nuanced level what exists around them, learn the ways in which things affect each other.

It was such a joy for me to be walked around a local forest with some local experts shortly after moving to northern California and talked through what all the most common native and invasive plants in the redwood ground cover were. Or seeing something new to me, and later coming across it at a native plant sale. Or visiting flushes of mushrooms I can expect to come up again and again every year. Memories of all of these kinds of things play out in my head every time I walk through the woods that reinforce my connection to these places. I would love it if my poetry could do some of those same things. Which is easier when writing about more beneficial plants or animals, but even with Field Guide, something to make people look at buckthorn and think “oh, that shouldn’t be here” or “Oh, I should remember this particular patch of holly for next time I’m back with a weed wrench.”

2. Invasive species seem to make great fodder for speculative fiction, weird fiction and poetry, as they can be viewed as both harbingers of dystopia and resilient survivors of ecological crisis. Do you think a new microgenre is emerging or that there is enough of this writing to constitute an emerging trend?

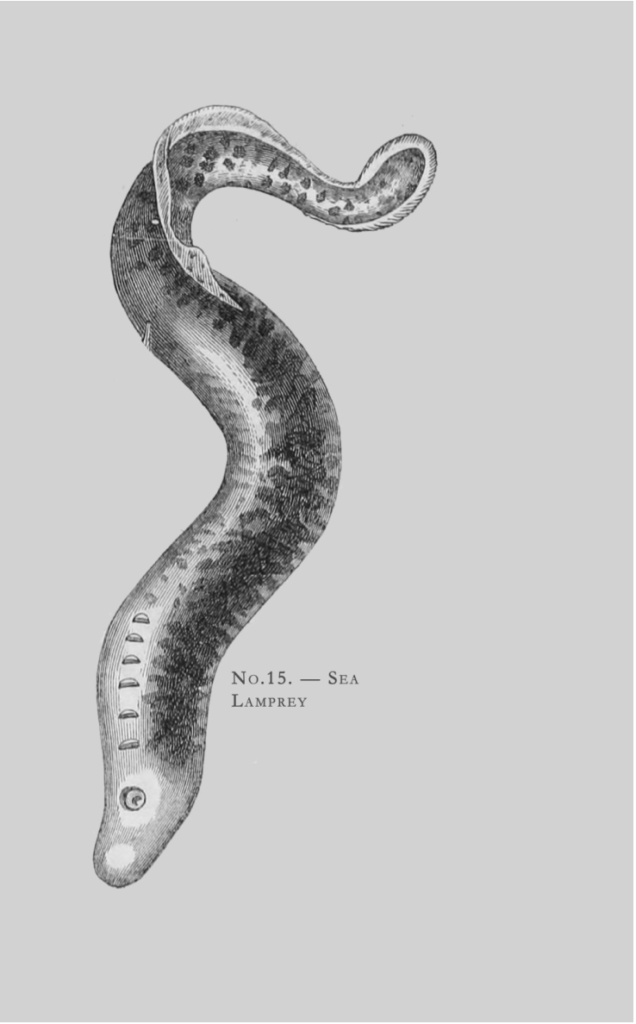

Yes, we’re definitely seeing a lot of ecological speculative fiction branch off into all kinds of very niche subgenres. Climate fiction, solarpunk, etc, and all of these are very future-focused. And even before people started consciously writing about the role invasive species play in habitat destruction, you could look at something like John Carpenter’s The Thing as laying some of the ground work for those new, emerging genres. The immense, practically incomprehensible size of a problem like climate change, or major extinction events also lends itself well to the Weird and you’ll see a lot of cross over in those genres as well. I’d also put any number of “gray goo” stories in this subset too – while not strictly about biological lifeforms, the story of even a mechanical, self-replicating thing that destroys all variety of life on earth has a lot of crossover too. Then you have Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, which is practically a microgenre in itself – and which probably strikes the best balance between a sense of deep loss and a respect for said ‘resilient survivors.’

3. How is writing about invasive species different from writing about native species, especially those that are at risk of extinction? Do you take a different creative approach?

It’s tricky, because I think writing about them wrong or clumsily could be read as a racist dog whistle and that’s something I definitely do NOT want to do. So I’ve always tried to stress that the problem with invasive species is the monoculture they create, and the loss of biodiversity.

And for better or worse, that shows a lot of the power of poetry. People go into it looking for not just deeper meaning, but with the assumption that it WILL have multiple meanings. Not everyone writes poetry that way, some poets do simply write to express the beauty of a thing, but I’m probably not one of them.

So I do want to do more than one thing, when I write about something. Writing about near-extinct species or disappearing eco-systems is something I always feel is fittingly paired with personal loss and grief. Or, for example, “Grecian Foxglove” in Field Guide, is also about how I don’t think short-sighted, quick-fix technological solutions are helpful.

4. You mention the DNR (Department of Natural Resources) in a couple of your poems. What role does the DNR play in your imagined post-apocalyptic future?

In my imagined future, it often exists as a ‘too little, too late’ attempt to reach out and put a bandaid on a giant, gushing wound. You see this in “Zebra Mussels” – definitely one of the more narrative poems in the book. It exists more to stave off unemployment in a world of increased automation than really do any proper zebra mussel eradication. All the individuals smashing zebra mussels in the world isn’t going to get rid of them if they keep being brought into new bodies of water. Or my little ivy group, while I mentioned later about how it does feel real and impactful to go save a tree, but it’s frustrating when people are still planting the stuff. I process donations and people have literally donated ivy and holly starters!

Being active in some volunteer groups, it’s often hard to really offer advice or support to extremely similar, adjacent groups – even with membership overlap – because so much depends on this very weird mosaic of jurisdictions. So, for example, while OUR ivy removal group might be able to get the city to donate use of a giant trailer for green waste and will advertise it on official city pages, the very next town over may not offer them the same resources. In the real world, I’d like to see larger organizations step in and cover the holes in what otherwise works well as a smaller, grassroots driven activity.

5. Are you in dialogue with other poets who incorporate invasive species into their work, like Maria Zoccola or Robin Gow?

Not with either of those two, though I’d love to get to know Maria Zoccola. I love that she also writes in a lot of speculative poetry – I think I was first introduced to her work from the Rhysling Award Nominee list (award from SFPA for best Speculative Poem of the year).

I recently had a great time guesting on a podcast (Shining Moon) with Priya Chand, writer and editor of Reckoning: A Magazine of Environmental Justice, who has also written about MN invasives and her work with removal groups. And Reckoning as a whole has just a lot of really powerful writing.

6. Your poetry chapbook is titled as if to be a real field guide and even includes illustrations of each species. Do you have a favourite field guide that you refer to (for native or invasive species)?

Yes, and I’d recommend writing in a Field Guide form for any poet who struggles to come up with titles or decide the order of poems in their manuscript. It was so nice to have that already decided for me.

For actual field guides, I got so into “Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast” by Christian Schwarz and Noah Siegel this past year – it’s kind of enormous to actually try to bring on a hike so we’re often more likely to leave it in the car and bring the mushrooms back to it. But it’s been so good for my mushroom identification skills. Instead of a traditional field guide, a lot of it is organized by similar looking mushrooms so it’s very easy to rule out common look-alikes. I know the authors have talked about how plenty of older guides dichotomous tree approach, or just straight alphabetizing can be harder to use. And the photos in it are just absolutely incredible. Plus its attention to detail in everything from spore prints to odor to microscopy. I saw the author give a talk on mushroom odor once and you could tell that was something he was especially passionate about. I’d love to find a similarly detailed book about mushrooms for when I’m back in Minnesota visiting.

I also have a waterproof seaweed guide from Backcountry Press that I love because I will fall on my ass in a tidepool more often than I should probably admit.

7. How are invasive species impacting your everyday life in your new home state of California? Have any inspired new poems?

I’m a member of a really wonderful group that does ivy removal from the redwoods. Occasionally other plants too – there’s a lot of crocosmia, holly, invasive blackberry, and pampas grass around here. Though I think removing the ivy is in a lot of ways the most rewarding. It’s a lot of fatalistic work that can often feel somewhat futile, but to cut an ivy growth that is already growing around a redwood, you actually get to feel a little bit of accomplishment. Like “hah, I just undid years of your work, ivy”.

I also love that I’ve started to see a lot of people at the tide pools with buckets gathering sea urchins. Whole families, even! While they are a native species, they’re aggressive and currently doing a ton of damage to the kelp here in California, largely due to a lack of natural predators/large sea-star die off. Their edibility (and even luxury) makes it more ‘fun’ for people to harvest them. That combined with early programs to breed endangered sea stars to release is pretty hopeful.

In the spirit of not being too nihilistic about the whole, I’ve been having trying to celebrate native California plants in poems and stories – I’m working on a series of speculative poems that imagine a crossover “planimal” plant animal hybrid that combines native species, such as the banana slug and silk tassel. I’ve also written a story about a landscape architect specializing in native plants in the Nightscript series from Chthonic Matter Press (vol. 6).

8. You mentioned doing a great deal of research on the invasive species you wrote about. If poets can draw from scientific literature, what do you think (or hope) scientists and land managers can gain from poetry?

Hopefully some enjoyment! When something becomes a job, I think it’s hard to stop and enjoy it. I feel this way about writing/reading sometimes – I’ll pick up a book of poetry and instantly be grilling myself on “what can I learn from this” or “what inspiration can I take from this” and really struggle with how to not see everything as an objective, or a self-improvement task and that it’s okay to simply step back and remember that you liked this stuff in the first place.

Poetry especially is good in situ – they’re tiny little books, small enough you can even sneak one in backwoods camping, that benefits from repeated rereading more than traditional novels or stories. I guess this ties back nicely into the first question – poetry can be just another layer of how you experience a place, or to remember it when you’re not there.