Stories about invasive species often tell of the challenges that are presented to our natural landscapes. While it may seem overwhelming at times, there are many stories that are instead driven by the success achieved by overcoming these challenges. We find that these stories can be even more important to share. The efforts that lead to these success stories, like the one we are looking into with you today, not only safeguard our natural spaces, but also inform us about how to respond to future forest pests.

The Asian longhorned beetle has made inroads in North American and European forests in recent decades, gaining it the reputation of being quite the voracious tree-eating insect. In June of 2020, the Asian longhorned beetle was officially declared eradicated from the City of Toronto and Mississauga by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency after a long management and eradication effort that began prior to the first detection of the insect in Ontario in 2003.

ALB was intercepted dozens of times at Canadian ports of entry between 1980 and 2003. Efforts from community scientists and quick Canadian Food Inspection Agency response kept us ahead of ALB until 2003 when a population was discovered in Toronto. ALB has made a worldwide name for itself as it is also a key forest pest of concern in European countries including Germany, France, Switzerland, and Italy.

These prior interceptions, compounded with an ALB infestation in Chicago that started in 1998, kickstarted a prevention effort among representatives from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the Canadian Forest Service, and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry. Cross-border collaboration was already ongoing when the first report of an ALB surfaced after being submitted by a community member who found the beetle of the windshield of their vehicle.

Quick Impacts & Biology

The Asian longhorned beetle is a wood boring beetle native to China and Korea. Experts think that it was introduced to North America inside wood packaging material. The adult insect is shiny black with prominent irregular white spots, long antennae with black and white banding. The insect, along with other members of the Anoplophlora genus leave characteristic large and circular exit holes on the trees it feeds on. Most of the detections of this beetle have been made by the public.

In North America, the ALB has a 1- or 2-year life cycle. It depends on when the eggs are deposited, temperature, and the quality of the host. And depending on the tree species, females can lay anywhere from 35 to 120 eggs. Larvae feed first in the cambium layer then burrow deeper into the heartwood. Peak emergence of the adult beetle from the host tree occurs in mid-June to mid-August.

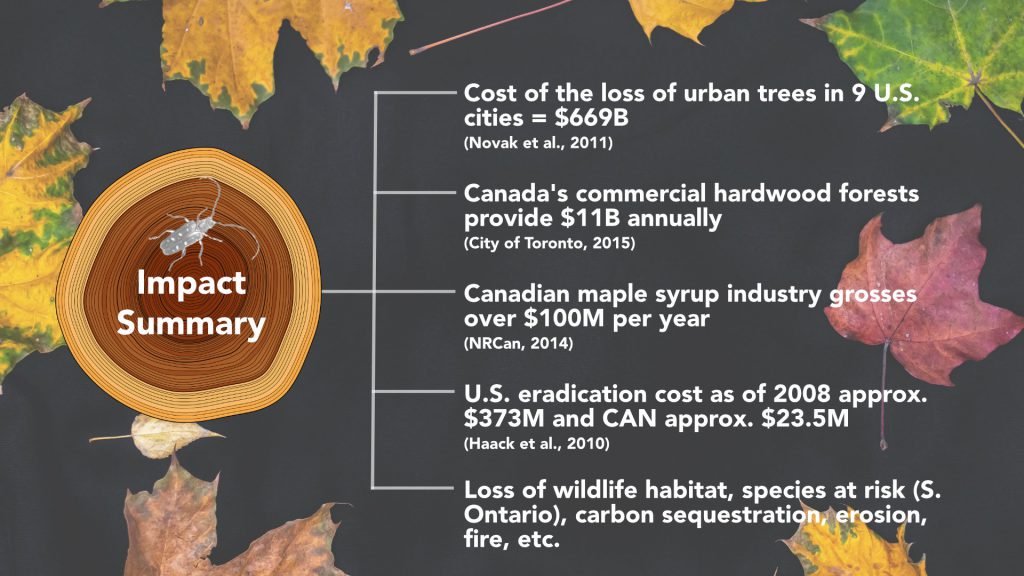

Why is the ALB such a high priority pest? It has no natural predators or parasites in the areas of North America that it has been introduced to. Several genera of trees and up to or greater than 20 species in each are susceptible to ALB attack. 42% of Toronto’s street trees are potential hosts for ALB. Two important things to predict potential infestation areas are maple trees and their proximity to roads. They do seem to have preference for maple. Other potential hosts include birch, elm, mountain ash, poplar, willow, katsura, and hackberry. The voracious ALB larvae feeding in the cambium and xylem is what causes trees to decline and eventually die.

The Response

Early detection and rapid response were very effective and successful in the case of ALB. The first detection in Canada happened in an industrial area north of Toronto in September 2003. Officials were already aware of the potential impacts of ALB on many of Canada’s native hardwood tree species, so were quick to make the decision to eradicate. Immediately, a 150 km2 quarantine zone was established around the initial detection site to restrict the movement of wood materials. By the following spring, 531 infested or likely infested trees were removed and destroyed, in addition to 12,500 high-risk trees in the regulated area.

After tree removal, the Canadian Forest Service and multiple survey crews continued to monitor trees within the regulated area looking for any signs of ALB. From 2004 to 2007, an additional 40 infested trees were detected and removed each year, less than 15 infested trees were found in 2007, and no infested trees were found for the remainder of the surveys. Over five years passed with no detectable signs of ALB in the area, and it was officially declared to be eradicated in April 2013 by the CFIA – a great success.

Unfortunately, the celebrations were short-lived. In December 2013, an adult beetle was collected and positively identified as ALB in an industrial area of Mississauga, outside of the original regulated area. Again, early detection of the new infestation allowed for rapid response by dedicated researchers and technicians. The area surrounding the detection was extensively surveyed, and technicians were able to locate two Norway maples and three Manitoba maples that showed signs of infestation. One of the Manitoba maples was heavily infested with over 900 exit holes!

Over the remainder of the winter, extensive tree removal took place in the new infested area. Tree removal efforts focused on four preferred tree hosts for ALB: maple, poplar, willow, and birch. Roughly 7,500 trees were removed in an 800 m buffer surrounding known infested sites. Each tree that was removed was carefully inspected by researchers for signs of ALB damage and then destroyed. Throughout this process, 25 more infested trees and 17 suspect trees were discovered. A new 46 km2 regulated area was established surrounding the infestation, and again, it was prohibited to move any tree materials out of the area.

Attention to detail during the rigorous surveillance work went a long way towards achieving a successful eradication programme. Technicians were suspended via boom trucks observing activity in the tree canopy while others zoomed in from the ground using binoculars. Researchers at the Canadian Forest Service came up with a novel approach to test the sharp eyes of the technicians by drilling counterfeit exit holes throughout the survey area so that certainty in inspecting actual ALB exit holes was ensured.

The Canadian ALB population showed interesting behaviour throughout the eradication effort. Host tree preferences varied between populations in Chicago and Ontario which led researchers to the conclusion that they came from different regions in Asia. They also noticed that ALB is not a frequent flier. ALB adults, if flustered, would fly out of the tree canopy and land in a safe place to then fly right back up to the same host tree. ALB were seen to feed on a single tree for several successive generations before finding a new one. Since this was the case, and since many detections of ALB were made near or on vehicles, it was deduced that cars and trucks were a key mode of transportation for ALB between the Toronto and Mississauga sites.

-

(Photos: Asian longhorned beetle exit holes on a Manitoba maple, courtesy of Aspen Zeppa, OMNRF) -

The Success

Dr. Taylor Scarr, Director of Integrated Pest Management at the Canadian Forest Service’s Great Lakes Forestry Centre, was an Entomologist with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry at the time of the Asian longhorned beetle response. Taylor notes that in order “to be successful in an eradication programme, you need to be early in your response, you need to be aggressive in your response, and you need to have a sustained response”. This eradication programme was successful in another way, in that the Canadian collaborators were able to produce data that aided their efforts and the efforts of friends across the border. While the strategy in the U.S. was centred on insecticide application, the strategic surveillance and cut-and-chip methods used in Ontario proved effective and were later replicated in Chicago and Massachusetts. In all, the Canadian partners involved, including the Canadian Forest Service, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry, the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture Food & Rural Affairs, university professors, local conservation authorities, the Cities of Toronto and Mississauga, alongside the Toronto area community, were able to see the project to the end. And to success! To date there have been no new detections in the area, so celebration is still in the air, however the partners aren’t letting their guard down.

Looking Ahead

In May 2019, the City of Edmonton was first alerted when a concerned resident called 311 after they saw a beetle emerge from a pallet in an industrial building. The city’s pest management lab quickly identified the bug as the first detection of ALB in Edmonton. Within 24 hours the lab placed traps near the site while the Canadian Food Inspection Agency worked to properly dispose of the wood in the shipment. The beetle has not been found in Edmonton since.

In late May 2020, an observant resident in Hollywood, South Carolina noticed and reported an unusual black and white spotted beetle near a porch light at their home. That beetle unfortunately turned out to be one of many Asian longhorned beetles infesting trees in the area, and USDA APHIS is now working with the Clemson Department of Plant Industry and Clemson Extension to understand the scope of the infestation, as well as how the beetle is spreading in this coastal South Carolina habitat.

While success stories in invasive species do exist, plants, animals and pathogens are more frequently being transported around the world, and travel and trade are one of the most common invasive species pathways. Any species could be liable to end up in a situation where they thrive unchecked by the natural predators and pathogens that would normally be present in its home range. Dedicated scientists, technicians, and all community members have a part to play in maintaining the health of our natural, commercial and urban forests, now and into the future.

-

Photos: Asian longhoned beetle (left) and white-spotted sawyer beetle (right). -

Want to help keep invasive forest pests like ALB from being introduced to or spreading in Canada? Follow these tips to help keep our trees invasive species-free:

- Learn to identify ALB, and to differentiate it from its native lookalike, the white-spotted sawyer beetle (above).

- Only use firewood sourced from local forests, and don’t transport it over distances of 80 kilometres.

- Check wood packaging materials of products that are of international origin.

- Avoid moving soil out of your area, as it could be filled with invasive plant parts, pests, or pathogens.

For more information on the Asian longhorned beetle and other species that affect forest health, visit the Invasive Species Centre website or check out this interactive story map created by University of Toronto Scarborough Master of Environmental Science students.