This guide is made to help you plan and find resources to fill your garden with stunning native plants that you and your family can enjoy and feel good about.

The Why

Introduction

In 2022, an official groundbreaking ceremony took place to unveil the future home of the Biodiversity Garden, a collaborative project in partnership with the City of Sault Ste. Marie, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library, and the Invasive Species Centre, with support from the province of Ontario.

This beautiful garden, located next to the Sault Ste Marie Public Library not only provides a great outdoor space for the community but serves as an example of how native plants can be used in horticulture to make a gorgeous space that is good for both people and the environment.

Native plant gardens are not limited to public spaces. You can create your own biodiversity garden at home which will benefit local wildlife, including pollinators, and prevent the spread of invasive plants which might harm the environment.

Why Biodiversity Matters

Biodiversity is a core component of healthy ecosystems. A common measurement of biodiversity is species richness, or the number of species found in an area. The more species found, the higher the index and the greater the benefits to the environment and to human beings.

A biodiverse ecosystem will be more resistant to stressors such as climate change because a greater variety of species allows ecological communities to adapt more readily to changes. Soil biodiversity is vital to plant health and benefits not only forests and wild spaces but is also important to agriculture as many crops rely on a diverse set of soil microorganisms to help them grow. Native species also serve as natural infrastructure. For example, wetlands and the plants that inhabit them are an important buffer against floods and storms.

Why We Should Plant Native Species – and Avoid Invasive Species!

Invasive species are defined as plants, animals, insects, and pathogens that are introduced to an area and cause harm to the environment, economy, or society. These organisms pose a significant threat to healthy ecosystems and in fact, invasive species are considered one of the top five major threats to biodiversity worldwide.

Invasive plants reduce biodiversity in several ways. Many invasive plant species tend to form monocultures (single-species stands) which push out native species and create large patches of land in which only the invasive species is present. They do this by outcompeting with native species for resources like light and water, usually because of rapid growth. Some invasive plants are allelopathic which means they can even produce chemicals that they emit from their roots which kill or inhibit the growth of other species. Examples of allelopathic invasive plants include garlic mustard, dog-strangling vine, common buckthorn, and Bohemian knotweed. These chemicals can also affect soil microorganisms such as arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi which native plants rely on for healthy growth.

Some invasive plants may even pose a threat to human health. For example, wild parsnip, an invasive plant, can be harmful when it comes in contact with skin or eyes.

Some invasive plants may even pose a threat to human health. For example, wild parsnip, an invasive plant, can be harmful when it comes in contact with skin or eyes.

Invasive plants can often be inedible for wildlife which means that when they replace native species, they are also reducing the food source for native fauna. Invasive plants like Phragmites can even cause socioeconomic damage when they grow out of control and block access to waterways and infrastructure or pose a danger to drivers when they impede sightlines on motorways.

Some invasive plants may even pose a threat to human health. For example, giant hogweed and wild parsnip both produce sap which can be harmful when it comes in contact with skin or eyes.

Another quality of invasive plants is their ability to spread and reproduce quickly. This means that if you have these plants in your garden, there is a good chance of them escaping into the surrounding environment and becoming established in local ecosystems.

Native plants that are already present in the wild do not pose this risk to the environment. They have evolved along with the local ecosystem and play a vital role in food webs and as shelter for native species. In fact, having native plants in your garden is beneficial to wildlife like pollinators which can use them as a food source.

Furthermore, there are several beautiful native plant species to choose from such as wild geranium, foam flower, wild strawberry and Michigan lily (in Ontario) which would make excellent additions to any home garden.

The How - How to Plan a Native Plant Garden

Step 1 – Get to Know Your Landscape

Before you begin planning your garden, it’s important to know what kind of habitat you’re working with. Plants differ in their needs including soil type and light levels and certain species may be happier in your garden than others. It’s also important to note what region you are in and what your local habitat type is because this will determine what native species are best to grow in your garden.

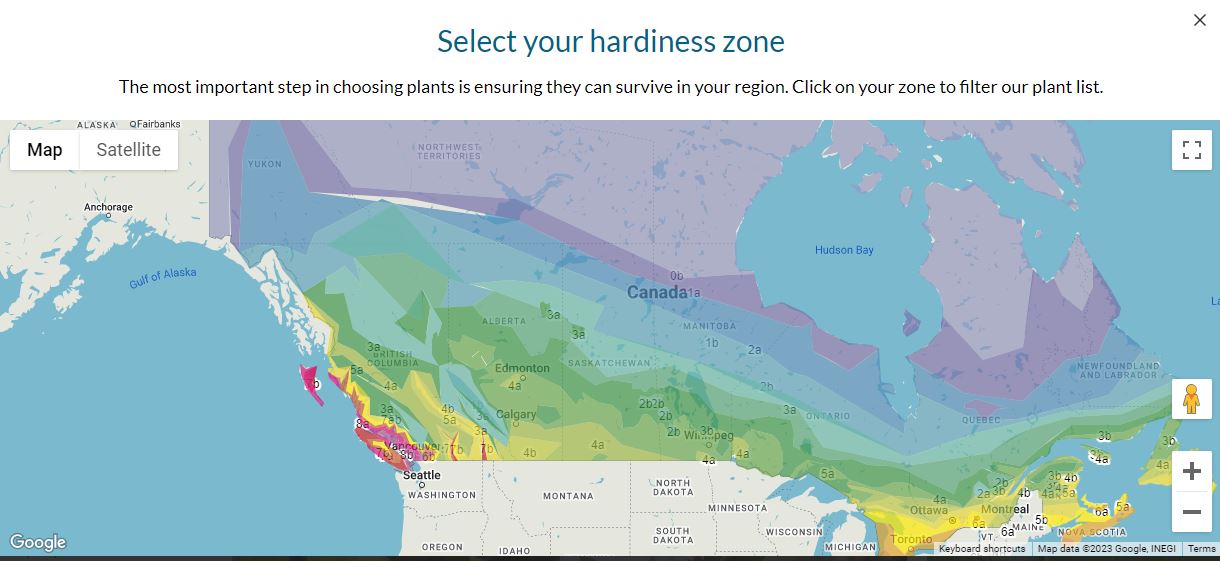

It’s important to note what region you are in and what your local habitat type is because this will determine what native species are best to grow in your garden. Image source: https://naturaledge.watersheds.ca/plant-database/

Knowing more about your local habitat will also help you to understand which native species (birds, insects, etc…) may benefit from your native plant garden and how to maximize these benefits. For example, in regions where monarch butterflies reproduce, it may be beneficial to add milkweed to your garden for them to lay their eggs on.

You may also want to consider what kind of space you’d like to create. Do you want a sunny, open yard with lots of flowers? Or would you prefer lots of trees, bushes, and shade?

Knowing your habitat type and what species are native to your region is especially important to ensure that:

a) you are using plants that will grow well in your garden

b) you are not spreading invasive plants

Some key questions to ask include:

- What type of habitat is my garden and what species are native to my region?

- How much light does my backyard get?

- What type of soil do I have?

- How much rain do we get? Am I able to supplement by watering my plants if needed?

- What native animal species would most benefit from my garden and how can I help them thrive?

- What kind of space do I want to create?

- How much work do I want to put in each year? (For example, do I want to have a garden with annual or perennial plants?)

Here are some helpful resources to help you get started:

Step 2 – Select your plants

Once you’ve determined what your habitat type and region is and what kind of space you’d like to create the next step is to find the plants that best fit into your garden.

Find Native Species.

The Ontario Invasive Plant Council has developed a Grow Me Instead guide for gardeners in Ontario. You can also ask your local garden centre about native plant options or order online from sources such as Northern Wildflowers (Northern Ontario) and Ontario Seed Company (Ontario).

Other sources for Ontario include:

Ontario Native Plant Nurseries

Grow Wild Native Plant Nursery

If you live outside of Ontario, native plant databases such as this database from Natural Edge and Watersheds Canada can also help you search for native species that fit your garden. To get started, select the hardiness zone associated with your location.

Be aware that not all plants sold in commercial gardening stores will be native to your region, and some may even be invasive depending on regional regulations. Asking questions and getting to know what species are local to your region is a great way to avoid inadvertently spreading invasive plants.

Buy local plants

It’s also important to ask about where their plants are coming from. Even if the plants they sell are native to your region, plants which are imported from far away may be carrying invasive pests from other regions that could be inadvertently introduced through your garden.

One example of such a pest is the jumping worm. Invasive jumping worms are transported to new habitats through mulch, compost, nursery stocks, or potting mixes from areas with established jumping worm infestations. These items can potentially tiny contain egg-filled cocoons. Their cocoons are difficult to distinguish from the surrounding soil or debris and once in the garden, worms can spread to surrounding natural areas and pose a threat to forest ecosystems.

Not all plants sold in commercial gardening stores will be native to your region, and some may even be invasive. Initially introduced to North America as a garden ornamental, Himalayan balsam is an invasive plant that has now spread accross Canada.

Step 3 - Learn how to properly dispose of invasive species yard waste

If you suspect you have invasive plants, insects or invertebrates such as jumping worms in your garden, it may not be suitable to dispose of your yard waste through compost. See our species profiles or best management practice database for more information on how to properly dispose of invasive species.

For regular yard waste, follow your local municipal guidelines.

Native Species Spotlight

Here are a few examples of beautiful native flowers and shrubs to inspire you. If you don’t live in Ontario, or want more information, check out the resources linked at the bottom for more ideas.

Flowers

Black-eyed Susan

(Rudbeckia hirta)

French name: Rudbéckie hérissée

Description: Yellow, daisy-like flowers with a black or brown centre. Its leaves are alternate and lance-shaped with bristly hairs. This flower grows up to about 1 metre in height.

Bloom period: Late July – September

Life cycle: perennial

Light conditions: Full sun or Partial sun

Soil type: Sandy, Loamy, Clay. Dry to moist; Drought tolerant

Soil pH: Normal

Ecosystem bonus: The flowers are beneficial to pollinator species, like bees and butterflies. The seeds are also beneficial to wildlife species, like birds and small mammals.

Wild Geranium

(Geranium maculatum)

French name: Géranium Sauvage

Description: Grows from 45 – 60 cm in height. The lower leaf surface has coarse white hairs and its flowers are pinks, white, or purple

Bloom period: Late spring to early summer

Life cycle: perennial

Light conditions: Full Sun or light shade. Plants flower more prolifically the more sun they receive

Soil type: Plant it in rich soil with plenty of organic matter and provide plenty of moisture for the best growth

Soil pH: Normal to basic

Ecological bonus: Great for pollinators and can provide shade for small animals

Spotted Joe-pye weed

(Eupatorium maculatum)

French name: Eupatoire maculée

Description: Spotted Joe-pye weed is a colourful wildflower species that can grow up to 1.5 m tall and can spread about 1 m

Bloom period: July – September

Life cycle: perennial

Light conditions: Full sun to partial shade

Soil conditions: Plant in rich and moist soil. It prefers sandy, loamy, or clay soil types and is tolerant of periodic flooding.

Soil pH: Acidic to normal

Ecological bonus: Attracts butterflies and other pollinators. The roots can be useful for controlling erosion and stabilizing shorelines.

Black Huckleberry

(Gaylussacia baccata)

French name: Gaylussaquier à fruits bacciformes

Description: A low shrub (typically 0.5 M in height) with yellowish green leaves that are oval and alternatively arranged. Flowers are bell shaped and white to light pink. Berries are bluish black when mature.

Bloom period: spring

Light conditions: partial sun

Soil type: sandy, loamy, or rocky; dry to normal moisture

Soil pH: acidic

Ecosystem bonus: The flowers attract and benefit pollinators, like bees and butterflies. The fruits can be eaten by wildlife species, like birds and small mammals and can also be consumed by humans

Eastern White Cedar

(Thuja occidentalis)

French name: Thuya Occidental

Description: Cones from the eastern white cedar are 7 to 12 millimeters long and grow in clumps of 5 or 6 pairs. Small scaly leaves cover the tree’s fan-shaped twigs and are a yellowish green colour. Due to its small size, the eastern white cedar is great for landscaping, primarily as a hedge tree

Light conditions: It prefers full sun and tolerates some shade

Soil type: Prefers moist, well-drained soil. Grows in a variety of soils but does not tolerate road salts. It grows throughout Ontario and is usually found in swampy areas where the rock underneath is typically limestone

Ecological bonus: The eastern white cedar is a small, hardy, slow-growing tree. It usually lives for about 200 years but can occasionally live much longer

Staghorn Sumac

(Rhus typhina)

French name: Sumac vinaigrier

Description: It is one of the last plants to leaf out in the spring with bright green leaves that change to an attractive yellow, orange, and scarlet in fall. Among the most recognizable characteristics are large, upright clusters of fuzzy red fruits that appear above the branches in late summer on female plants. Staghorn Sumac’s can grow up to 6 m high, 10 cm in diameter and 50 years old

Light conditions: Full sun, 6 hours direct light daily

Soil pH: Tolerates alkaline soil, clay soil and road salt

Soil type: Well-drained soil, tolerates dryness

Bloom period: Late spring/early summer

Ecological bonus: They are highly appealing to birds

Resources

Ontario Specific

The Ontario Invasive Plant Council has developed a Grow Me Instead guide for gardeners in Ontario

Going Wild for Native Plants – Ontario Nature

Ontario Native Plants | Native Plant Nurseries | Ontario

Ontario and Beyond

Funding Partnership

The Biodiversity Garden is a collaborative project in partnership with the City of Sault Ste. Marie, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library, and the Invasive Species Centre, with support from the province of Ontario.