Photo from AgriLife Today

In July 2022, Entomological Societies of Canada and America adopted the name northern giant hornet as the new common name for the species Vespa mandarinia. You can read the Entomological Society of America’s press release here.

The Invasive Species Centre will be transitioning our materials from “Asian giant hornet” to northern giant hornet. We will be sharing information about this change at events and in our resources.

Formerly known as: Asian giant hornet

French common name: Frelon Géant du nord

Order: Hymenoptera

Family: Vespidae

Northern giant hornets are native to temperate regions in China, Korea, Japan, and India. Along with their name and aggressive appearance, their size is quite intimidating, ranging from 3.5 to 5 cm in length. This qualifies them as the largest species of hornet in the world (Government of Ontario).

These hornets were first spotted in Canada in August 2019 on Vancouver Island. Following the first sighting, a pest alert for northern giant hornets was issued by the Ministry of Agriculture in British Columbia (Invasive Species Compendium). They pose a threat in their non-native range as they feed on native insects such as butterflies, dragonflies, beetles, and many others.

Did you know?

Northern giant hornets are commonly referred to as ‘murder hornets’ in the media. Their name has led the public to believe they present a terrible danger or threat to humans. Contrary to popular belief, they got their nickname from their predatory habits towards insects. They will only attack humans if their colonies and nests are being threatened, so it is important to take appropriate precautions when coming across a nest or habitat where these hornets live.

General Information

Northern giant hornets are well named as the world’s largest hornet. A queen’s body length can grow to exceed 5 cm (2 inches), the width of a driver’s license, with a wingspan that can exceed 7.6 cm (3 inches), the length of a driver’s license. Male and female workers look very similar but are smaller at 3.5 to 3.9 cm (1.5 inches) in body length.

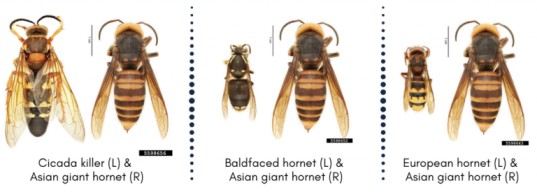

Their colour is distinctive – you should look for orange-yellow heads, a black or dark brown thorax, and striped abdomens – with alternating bands of orange-yellow and black or orange-yellow and brown. The stinger region is entirely yellow. In North America, there are several native, naturalized, and invasive insects that are commonly confused with the northern giant hornet including the European hornet and eastern cicada killer.

Photo credit: Shirley Xanthe, USDA

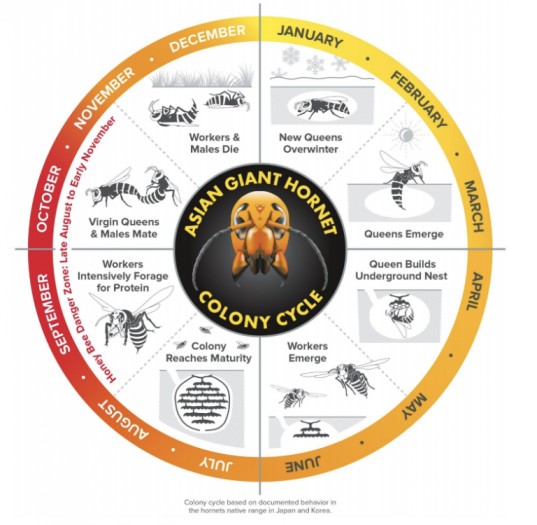

After a long winter underground, the northern giant hornet queen emerges in late April to early May and begins to establish her new nest in the ground. The queen forages and performs all the work including constructing the nest, egg-laying, and caring for the young.

These tasks are then passed over to the first set of workers who emerge as early as June and take over the duties within two to four days. The queen then focuses solely on laying eggs while the workers focus on foraging, attending the queen, and constructing larger cells in the nest.

By the end of August through October, only the queens and males (drones) are reared. During this stage, the workers will start attacking other insects to meet the growing food demands of the colony. It is during this time that mating occurs and the founding queen of the nest dies. No new workers are emerging, and the nest begins to die out.

After this, inseminated queens search for their ideal location to overwinter and the cycle repeats in the springtime (Cobey S et al., 2020).

Photo credit: The Asian Giant Hornet: What the public and beekeepers need to know

Northern giant hornet colonies nest underground together with one queen and many workers. Being underground, colonies are typically difficult to locate. They create nests underground in a variety of ways including digging, occupying pre-existing tunnels, and using spaces by tree roots.

In terms of the overall ecosystem this species prefers, they tend to gravitate towards low forests and mountains, and avoid high-altitude climates and plains (Pestworld.org).

Photo credit: Smithsonian Magazine

Since northern giant hornets nest below the surface, nest sightings are not common. Seeing the hornet itself will be the first sign that there is a potential outbreak.

Photo credit: Hanna Royals, Museum Collections: Hymenoptera, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org

Proper identification and reporting can help with this, as they are commonly mistaken for native or naturalized hornets in Ontario such as the European hornet (Government of Ontario). The graphic above can be helpful in safely identifying these insects.

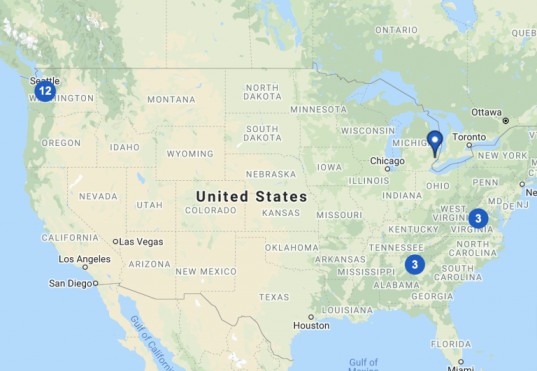

Northern giant hornets are native to Southern Asia, from India through China, into Japan and Korea. They are known for inhabiting the lower altitude forest and avoiding large plains and high-altitude regions. They have been found in the Nanaimo, BC area (August 2019) as well as south into Washington state (December 2019). Research is currently underway to track and identify whether the northern giant hornet will spread over the Rocky Mountains without human assisted movement.

The map below is the EDDMapS (Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System) distribution map for the northern giant hornet as of July 2021. To see the current EDDMapS distribution map, click on the map below.

Map from EDDMapS. 2021. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia – Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed July 28, 2021.

Impacts

Northern giant hornets feed voraciously on other arthropods. In North America they mainly feed on native insects: butterflies, moths, dragonflies, bees, wasps, etc. As well as putting many native insects at risk, the feeding habits of northern giant hornets can reduce the germination rates of native plants as they feed on the pollinators they rely on.

Northern giant hornets can have large impacts to pollinators, which reduces crop yields. As well as impacting the food industry, hikers and other recreational activities can be affected by these hornets. If the nests are disturbed, northern giant hornets can become aggressive and territorial, chasing hikers away from trails.

A recent European study analyzed the cost of fighting the invasion of the northern giant hornet (which essentially consists of the cost of nest destruction). The research team studied information about the companies providing the nest destruction services, extrapolated the cost of nest destruction spatially and modelled the potential distribution of the invasive. The calculations show that the estimated yearly cost for eradication would be $44.6 million Canadian for three European countries (Barbet-Massin et al., 2020).

Management

The prevention of spread of these invasive hornets is the most crucial control method. This includes destroying nests when found, trapping, and physical or chemical destruction. These methods are all to be done AFTER properly being reported and only by a professional (Government of Ontario).

How to report a sighting of northern giant hornets or their nests:

- In Ontario, report to eddmaps.org or the Invading Species Hotline on 1-800-563-7711

- Check our website for all other provinces: https://www.invasivespeciescentre.ca/Report-A-Sighting

- Provide a photo if it is possible to take it safely

By learning how to properly identify and prevent the spread of northern giant hornets, we can protect ecosystems and insect species from this pest!

Further Reading and Resources

Cobey S., Lawrence T., Jensen M. (2020). The Asian Giant Hornet – What the Public and Beekeepers Need to Know. Washington State University. Retrieved from https://research.libraries.wsu.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/2376/17934/FS347E.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Barbet-massin, M., Salles, J.M., Courchamp, F. (2020). The economic cost of control of the invasive yellow-legged Asian hornet. NeoBiota. 55:11-25. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.55.38550.

Government of Ontario – Control Methods

Wilson, T., Looney, C., Tembrock, L. R., Dickerson, S., Orr, J., Gilligan, T. M., & Wildung, M. (2023). Insights into the prey of Vespa Mandarinia (hymenoptera: Vespidae) in Washington State, obtained from metabarcoding of larval feces. Frontiers in Insect Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/finsc.2023.1134781