Chestnut Blight (Cryphonectria parasitica)

Chestnut blight canker

Credit: William Powell, American Chestnut Foundation

French common name: Brûlure du châtaignier

Order: Diaporthales

Family: Cryphonectriaceae

Did you know? American chestnut trees are listed as endangered in Ontario after the introduction of chestnut blight.

Description

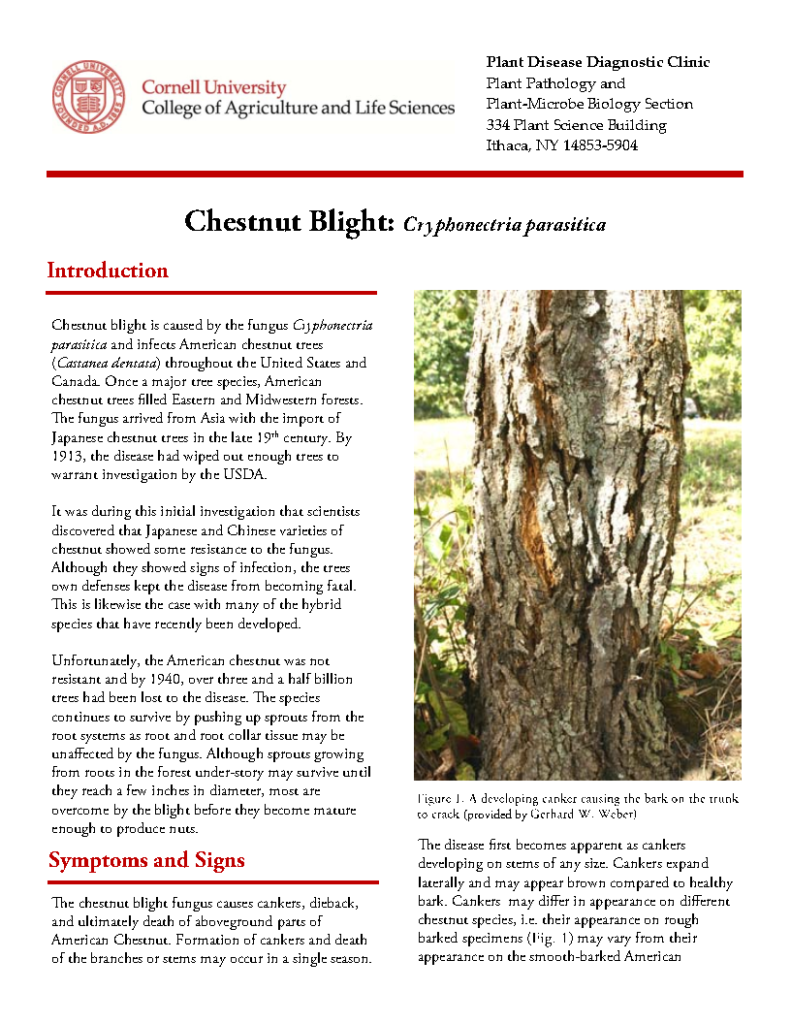

Chestnut blight is an invasive fungal pathogen that devasted American Chestnut in Canada and the United States. It was first documented in 1904 when a forester noticed dying chestnut trees in the Bronx Zoo in New York City. A mycologist later assessed the site and was able to identify the chestnut blight fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) on infected trees, which explained their rapid mortality. Chestnut blight causes cankers that girdle the tree and block the transport of water and nutrients, leading to tree death in about 1-3 years.

The pathogen was introduced to North America on infested Japanese chestnut nursery stock imported from Asia. These trees were widely distributed when sold to nurseries across the United States, enabling the fungus to spread throughout the entire range of American chestnut by the 1930’s. Chestnut blight reached southern Ontario in the early 1920s, where it decimated native American chestnut throughout the Carolinian Zone. This is the most biologically diverse and fragile ecoregion in Canada, supporting more than 500 rare species alone. Within the span of about 30 years, 99% of American chestnut found in North America were killed from chestnut blight, with as estimated 3.5-4 billion trees lost in the United States and up to 2 million lost in Ontario.

Chestnut blight is a bark pathogen, killing only the aboveground portion of the tree. Since the root system remains uninfected, living roots will often produce sprouts even after infection. Most sprouts are infected with the blight before they can mature enough to produce seeds, but some survive longer and grow to be a few inches in diameter.

There has been action taken in Ontario in efforts to restore American chestnut and develop blight-resistant trees. While there have been promising results, chestnuts remain vulnerable to this lethal fungal disease.

- The fungus parasitica requires fresh wounds, growth cracks, or dead bark (caused by factors such as fire, drought, or other damage) to enter new host tree tissues.

- Fungal spores spread locally by wind, rain, insects, and small animals, and over longer distances by birds.

- Spores will germinate in host tree tissues to start a new infection.

- Mycelium grows and spreads into the cambium, which is the tissue layer with actively dividing cells responsible for continued tree growth.

- Cankers form and spread rapidly at the site of infection, girdling and killing branches and trunks.

- Fruiting bodies form the following spring on the canker and surrounding bark.

- Young trees may die within a year, while mature trees may take years to die from the fungus.

- The fungus does not infect the crown or roots. The living root system can regenerate to produce sprouts that grow into small trees. These trees can sometimes grow large enough to produce a few nuts before being re-infected by the blight.

While many tree species in the family Fagaceae can become infected with the chestnut blight fungus, American chestnut appear to be the most susceptible. European chestnut are also vulnerable to infection but are not as high risk as American chestnut. In contrast, Chinese and Japanese chestnut trees seem to be the more resistant and do not show serious symptoms when infected.

Some species of oak are thought to be potential secondary hosts for chestnut blight (since they’re in the Fagaceae family), but no serious impacts have been recorded.

- Cankers: Reddish brown cankers form on stems of any size and can be visible at any time of year. They expand laterally and may look swollen or sunken. As the canker matures, the bark swells, cracks, and eventually falls off. Superficial cankers that heal fast and appear dark brown or black in colour are sometimes observed.

- Dieback: Stem girding above the canker, leading to branch wilting and rapid dieback.

- Epicormic shoots: Shoots develop below the canker in response to stress and from the stump after tree death.

- Fruiting bodies: Small yellow orange to red fungal fruiting bodies form in the bark cracks and cankered tissue.

- Leaf discolouration: Leaves may turn yellow or brown and wither from lack of water, but often remain attached to the tree until late fall. Some dead leaves may remain attached throughout the winter.

Left photo: Chestnut blight canker. Credit: Richard Gardner, Bugwood.org.

Right photo: Fruiting bodies created by chestnut blight fungus. Credit: conboy. 2024. iNaturalist observation. Accessed on 6/3/2024.

Photo: Leaf discolouration from chestnut blight. Credit: Andrej Kunca, National Forest Centre – Slovakia, Bugwood.org

Photo: Leaf discolouration from chestnut blight. Credit: Andrej Kunca, National Forest Centre – Slovakia, Bugwood.org

American chestnuts are often confused with other tree species, such as horse chestnut, chestnut oak, chinkapin oak, and beech.

Left photo: American chestnut leaves. Credit: pcatling. 2023. iNaturalist observation. Accessed on 6/3/2024.

Right photo: Horse chestnut leaves. Credit: g_buck. 2023. iNaturalist observation. Accessed on 6/3/2024.

There can be other pests or pathogens that interact with chestnut to cause declines in health. For example, invasive chestnut gall wasps lay their eggs in the buds of chestnut shoots, resulting in the formation of galls. The chestnut blight fungus can enter tree tissues from the wounds created by abandoned galls, resulting in tree stress and mortality.

There are diseases that impact the health of different tree species that sometimes produce symptoms like that of chestnut blight. For example, the fruiting bodies of beech bark disease, an invasive pathogen complex that threatens beech, can look quite similar to the fruiting bodies of chestnut blight.

These chestnut blight look-a-likes may be native diseases that are a natural part of the ecosystem processes, or they could be another invasive species as explained in the examples above. If you suspect that a diseased tree could be impacted by an invasive pathogen, it is important to report it to the correct authorities. Experts will be able to accurately identify the disease and implement action if required.

You can use digital tools such as EDDMapS or iNaturalist to aid in species identification and reporting from your smartphone.

In North America, chestnut blight can be found throughout the entire range of American chestnuts. In Canada, American chestnut, and therefore chestnut blight, are only found in southwestern Ontario’s Carolinian Zone between Lake Erie and Lake Huron. American chestnuts used to dominate the area, but numbers have drastically declined since the introduction of chestnut blight. The disease has also been confirmed on a small number of ornamental chestnut trees in British Columbia. In the United States, chestnut blight can be found on native chestnuts ranging from Maine to Mississippi.

A map produced by the American Chestnut Foundation shows the progression of chestnut blight through the range of American chestnut in Eastern North America.

The American chestnut is considered an endangered species under the Species at Risk Act (SARA). In response to this change in status and in efforts to protect this tree species, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and Environment Canada created a detailed recovery strategy.

The recovery strategy includes the following objectives:

- Survey suitable habitat and/or formerly occupied habitat for American Chestnut, and protect and monitor known populations within the species’ native range in Ontario;

- Promote protection and public awareness of American Chestnut;

- Develop and evaluate management measures to control threats; and

- Secure Ontario sources of germplasm originating from blight-free trees.

Click here to learn more about the progress made towards the protection and recovery of American chestnut in Ontario.

In the United States, the devastating outbreak of chestnut blight and loss of American chestnut trees led to the development of The Plant Quarantine Act in 1912. This act aims to reduce future ecological invasion catastrophes and gives the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) the authority to regulate the movement/importation of nursery stock and other plants that may carry pests and diseases harmful to US agriculture practices.

Economic Impacts

The American chestnut tree once accounted for almost 50% of the eastern deciduous forests of North America. In 1912, when chestnut blight was infecting chestnut stands and the concern for the tree was elevated, the United States government determined the chestnut stands at risk of mortality in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and North Carolina were worth $82.5-million USD (Holmes et al., 2009). In present economic terms, those trees would be worth over $2-billion USD ($2.5-billion CAD).

The American chestnut was used in several manufacturing and lumber industries. The tree once accounted for 50% of the tannin used by leather processing industries. Additionally, it is a reliable, durable, straight-grained wood that posses strong rot-resistant qualities. It was used for barn and house posts and beams, bridge timber, floors, doors, windows, railroad ties, and exterior sidings and trims as the wood contained weather-resistant properties.

American chestnut are protected in Canada and therefore no longer harvested, though chestnut wood from abandoned barns and sheds are sometimes repurposed to be used again.

Environmental Impacts

The American chestnut can live up to 500-years and can grow up to 30-m in height. A mature female tree can produce 3000 to 6000 nuts per year and is an excellent source of food for humans and wildlife such as squirrels, parakeets, bears, deer, elk, and turkey. Chestnuts were even preferred by the now extinct passenger pigeon.

Recent studies suggest there are around 1000 mature and up to 150 small young American chestnuts present in Ontario today. While American chestnuts often sprout from their living roots, it can be difficult for them to reach maturity without being re-infested by the blight. Cross-pollination of mature trees can also be challenging since many trees have become geographically isolated from chestnut blight mortality.

Social Impacts

Many people in North America relied on the American chestnut for food. Unlike most acorns and nuts that need to be boiled, the chestnuts from these trees can be eaten immediately after harvesting. Chestnuts are also high in carbohydrates and protein and can be dried then stored for long periods of time (making them especially useful for livestock feeding through the winter). The abundant and constant supply of chestnuts were a stable source of income for many people.

American chestnuts are also medically valuable. For example, the tree leaves contain high tannin concentrations, which were often used to make teas to aid respiratory diseases (i.e. whopping cough).

Prevention

When chestnut blight first appeared in North America, farmers and foresters were encouraged to immediately cut down and burn all infested trees to prevent further spread. Chestnut blight spread rapidly on the landscape, and unfortunately these attempts to contain the disease were unsuccessful.

How can you help now? One of the most important things you can do is learn how to identify American chestnut trees. Healthy mature trees are quite rare and may have somehow escaped fungal infection. Reporting the presence of these trees is critical to retain biodiversity and learn more about species distribution.

Detection

Reporting sightings of American chestnut, along with other species of conservation concern, can help provide a better understanding of biodiversity and forest health.

If you’ve found an American chestnut tree, report it immediately to the Natural Heritage Information Centre by using their Observation Reporting Form or by joining the (NHIC) Rare species of Ontario project on iNaturalist.

Report any signs or symptoms of chestnut blight to EDDMapS.org.

Chemical Control

Large-scale chemical control of chestnut blight is impractical in forest settings where the rate of spread is high. Chemical treatments applied by trained arborists in smaller areas (e.g., private properties) have had some success, but do not cure the tree or prevent death.

Biological Control

Resistance breeding

The Canadian Chestnut Council, a non-profit dedicated to the preservation and restoration of American chestnut, launched a breeding program in 2000 to breed self-sustaining blight resistant trees adapted to Ontario. In an effort to maintain the Canadian population, the program crosses native American chestnut with pollen of known resistant trees. This work is ongoing, though initial results show promise.

The American Chestnut Foundation has completed similar work in the United States by breeding blight resistance Chinese chestnut with American chestnut. In these tests, the resulting trees that are 50% American and 50% Chinese were then backcrossed with American species. This process is repeated several times in an effort to maintain as much of the American chestnut as possible.

Hypovirulence

Hypovirulence control measures, which involve the use of a virus to reduce fungal disease effectiveness, have been successfully implemented in Europe, allowing European chestnut to re-establish over time. The virus infects C. parasitica (the fungal pathogen causing chestnut blight) and reduce its ability to infect host tree tissues.

This technique has been met with limited success when tested in North America. There are a few possible explanations for this difference in outcome:

- European chestnuts are more blight-resistant than American chestnuts. The high susceptibility of American chestnuts to parasitica often leads to tree death before the hypovirus can infect the fungus (Rigling & Prospero, 2018).

- European forests experience less hardwood competition than North American forests. For example, one study found that decreasing hardwood competition increases American chestnut survival against chestnut blight (Griffin et al., 1991).

There is ongoing research to better understand hypovirulence and the role it could play here in North America.