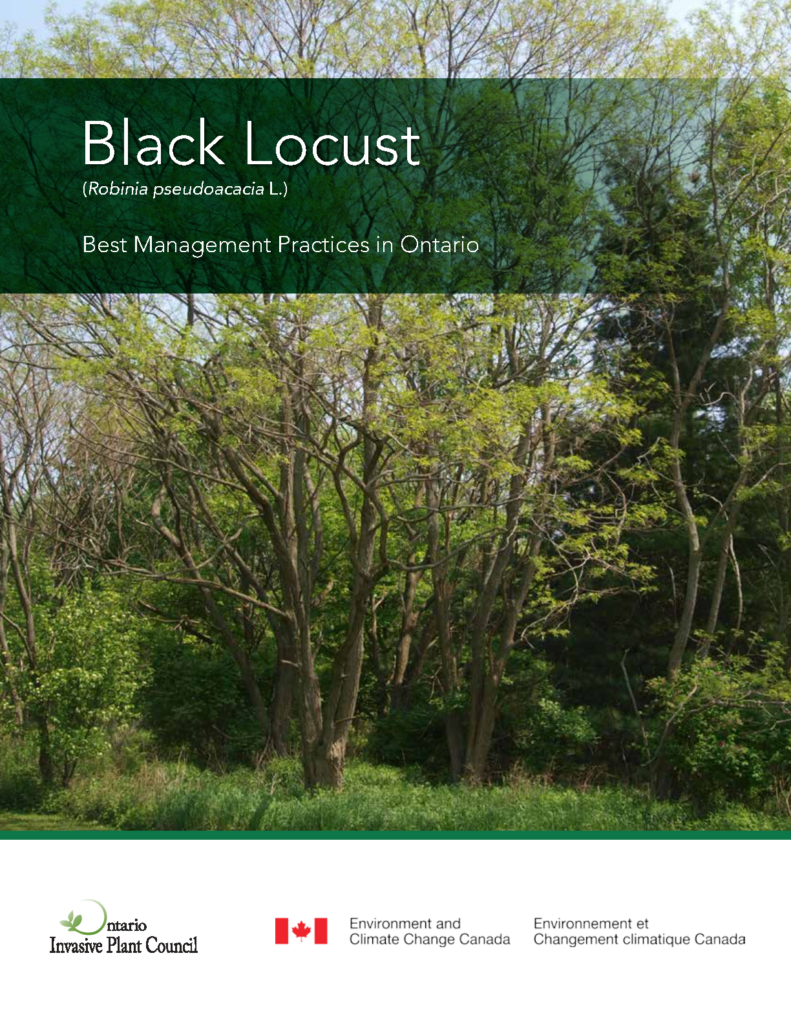

Black Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

French common name: Robinier faux-acacia

Black Locust Tree

Image by: Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org

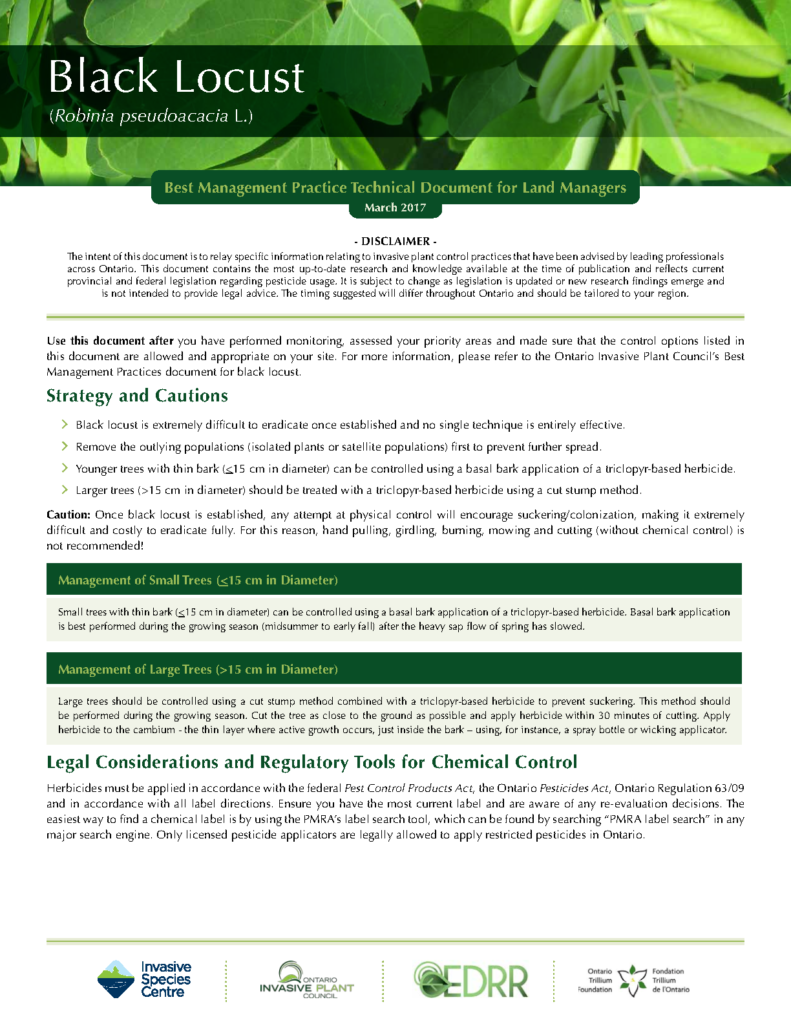

Black locust leaves and flowers

Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org

Other English Common Names: false acacia, post locust, and yellow locust

Order: Fabales

Family: Fabaceae

Subfamily: Faboideae

Did you know? Many parts of black locust, including the stems, leaves, bark, and seeds, contain a gastrointestinal neurotoxin that can be hazardous to several mammal species, notably horses and humans. In some cases, ingestion of black locust can be fatal.

Introduction

Black locust is a medium-sized tree native to the Appalachian region of the United States. It propagates easily by seed, coppice, and root suckers and is an aggressive pioneer species (species that are first to establish in new environments). For this reason, it tends to grow better in open vegetation type habitats such as prairies, meadows and savannahs, as well as in disturbed habitats such as pastures, degraded woodlands, thickets, old fields, forest edges and roadsides.

Landowners will sometimes plant black locust because it’s a rot-resistant, hardy plant that can be quite effective in controlling erosion. For this reason, it is primarily spread via human activity through the horticulture pathway. Consequentially, black locust has been spread globally to every continent except Antarctica, and it has become invasive in many places, including parts of Canada. The introduction of this species is detrimental to local ecosystems as it pushes out native vegetation, alters soil properties, and negatively impacts species at risk.

Management of black locust can be difficult, as mechanical methods such as pulling, girdling, burning, mowing, and cutting will encourage suckering (development of new shoots, or “suckers,” from the base of a tree or shrub, or from the root system). Chemical control methods are available in some circumstances (see management section below) but prevention and early intervention are the best strategies to protect the environment and reduce economic costs.

General Information

Black locust is a medium-sized tree, averaging 12 to 30 m in height and 30 to 60 cm (up to 150 cm) in diameter. Its crown is narrow with an open, irregular form and contorted branches. They tend to grow straight in forests but may grow curved in open areas.

Leaves

The leaves have one main stem with smaller leaflets arranged on both sides. There are 3 to 9 pairs of smooth, oval leaflets, plus one leaflet at the end (pinnately compound).

Flowers

Flowers are white, clustered in groups of 10 to 25. Each flower is 2 to 2.5 cm across and flower clusters are 10 to 20 cm long.

Seeds

Seeds are smooth, flat, and dark brown, measuring 5 to 10 cm long.

Bark

Older trees have grey-brown, thick, deeply furrowed bark. Younger trees have smooth, brown or greenish bark and will have conspicuous lenticels (pores) and spines.

A few tree and shrub species may be mistaken for black locust including prickly ash, Kentucky coffee tree, false indigo, honey locust, and prickly locust. See the Black Locust BMP booklet for more information on these species and how they differ from black locust.

Black locust propagates easily by seed, coppice and root suckers and is an aggressive pioneer species, meaning it’s usually one of the first to establish in new environments. Damage to the roots or stem may promote the formation of these suckers, making management difficult. It establishes well in early-successional communities where it often grows in dense thickets or clonal colonies (black locust trees that have originated asexually from one single tree). Generally, the oldest trees are located in the center and youngest trees on the edges of stands. In its native habitat (Appalachians), black locust grows primarily on slopes and is usually an uncommon species in late successional communities, occurring only at low densities.

As a pioneer species, black locust can survive in a variety of ecosystem and soil types, including nutrient poor soils, readily colonizing disturbed or damaged ecosystems. It is adaptable to environmental extremes such as drought, air pollutants and high light intensities. It is also cold hardy and tolerates a wide range of pH levels. This species favours humid to super-humid climates but can tolerate a range of moistures because of lateral and vertical roots that can withstand weather extremes, such as prolonged droughts, giving it an advantage over many native species.

Despite its hardiness, black locust does not thrive in all environments, especially in late stage and climax forest communities. Black locust is generally intolerant of:

- Shade

- Species competition

- Frost/cold temperatures (Although black locust is moderately frost hardy in the Southern and Central Plains, cold weather damage has occurred in the colder parts of its range and it is highly susceptible to frost in the Appalachian region).

Consequentially, black locust tends to grow better in open vegetation type habitats such as prairies, meadows and savannahs, as well as in disturbed habitats such as pastures, degraded woodlands, thickets, old fields, forest edges and roadsides.

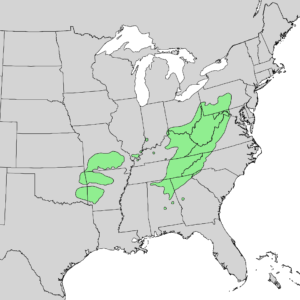

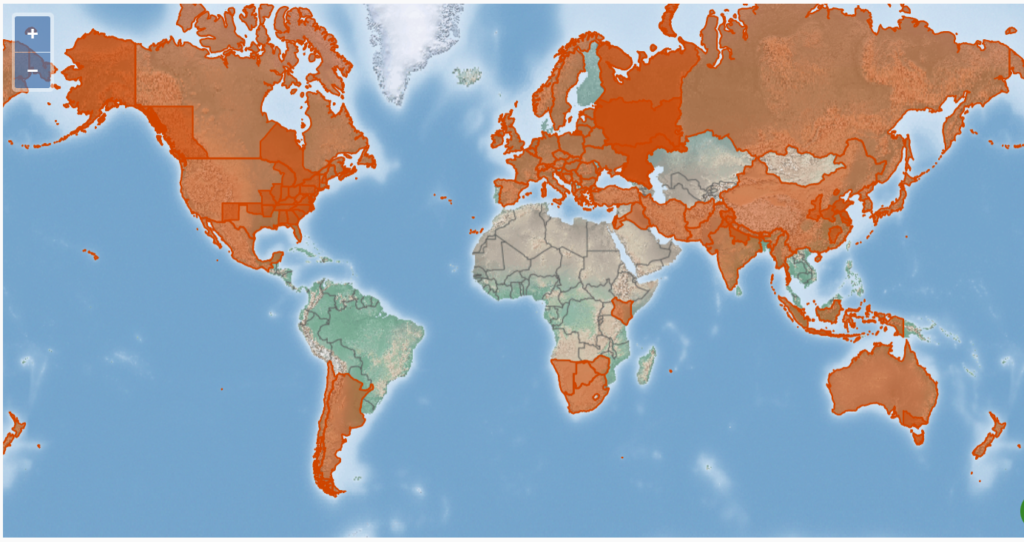

Black locust is native to the Appalachian Mountains and Ozark Plateau of the United States, with its native range extending from central Pennsylvania to Alabama and Georgia. The widespread use of black locust for ornamental, forestry, shelter, and land reclamation purposes has caused it to become naturalized or invasive in many regions.

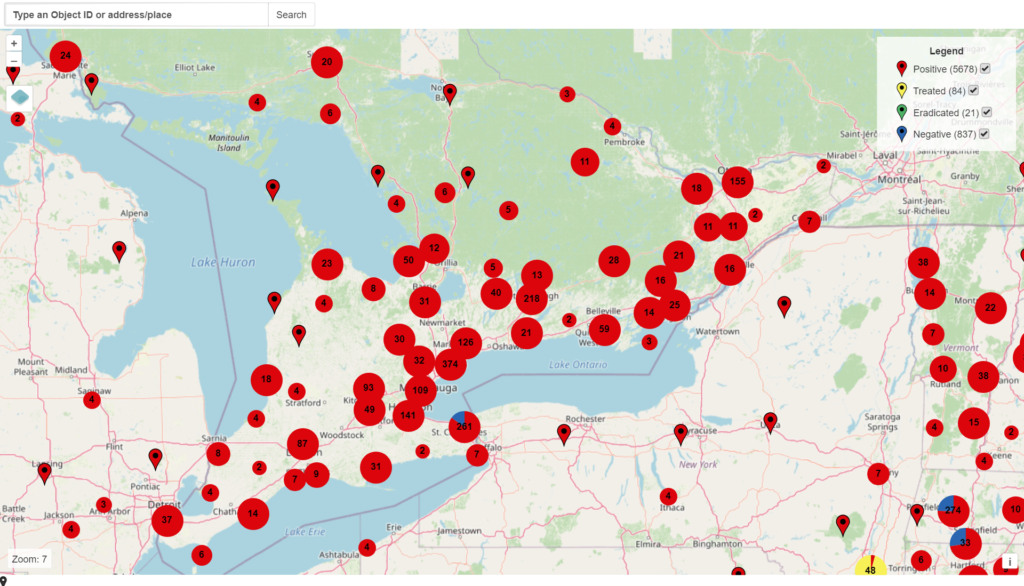

Within Canada, black locust has spread to Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia. In Ontario, black locust is most abundant in southern Ontario but can be found as far north as Sudbury and as far West as Sault Ste. Marie.

Globally, black locust has spread to every continent except Antarctica, and it is considered invasive in several countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, South Africa, Namibia, and parts of Europe.

Environmental Impacts

Black locust invasions can significantly harm Ontario’s native ecosystems and species, including those at risk. Black locust can affect natural ecosystems and native species in several ways including through competition for resources, alteration of soil chemistry, habitat modification, and disruption of pollination.

The replacement of native communities by homogenous and low-diversity communities of pure black locust stands causes both plant richness loss and shifts in species composition. This is especially concerning for the species designated under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) as being extirpated, endangered or of special concern in Canada. Some SARA plant species impacted by loss of habitat due to black locust include pink milkwort, white prairie gentian, skinners agalinis, and showy goldenrod.

Black locust is particularly problematic in pine barren, sand prairie and black oak savannah plant communities It aggressively invades ecosystems such as oak (Quercus spp.), beech-maple (Fagus sp. – Acer spp.) and aspen (Populus spp.) forests, and already fragmented native prairie and savanna ecosystems, where it forms dense colonies and shades out native plants, causing floristic homogenization (the increasing similarity of species composition over time). The roots of the black locust have nitrogen fixing nodules that can increase the nitrogen content in the soil, altering ecosystem structure and dynamics and causing a decrease in species richness. Phosphorus and calcium levels are also elevated when black locusts are present. This can lead to secondary invasions, as in low nutrient habitats, introducing high amounts of these nutrients provides ideal habitat for non-native, nitrogen-loving weeds, resulting in an altered succession pattern.

Native plant reproduction may also be affected by black locust. The flowers of the black locust are favoured by pollinators and there is concern that black locust’s abundant nectar may attract pollinators away from native species that flower at the same time.

Social and Economic Impacts

Many parts of black locust, including the leaves, inner bark, young shoots, pods and seeds, are toxic to humans and many animals. Black locust leaves, stems, bark and seeds contain gastrointestinal neurotoxins which can harm mammals, especially horses. Some symptoms to lookout for in horses include depression, lack of appetite, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and laminitis. It is therefore recommended that black locust trees are removed from/not planted in pastures which will contain livestock.

Black locust management is economically costly. This tree reproduces through seeds but is extremely inclined to colonization through suckering (producing a number of new root sprouts), making physical control methods difficult and often impractical.

Black locust spreads rapidly and established populations are very difficult to control. No single technique has been identified as entirely effective; therefore, early detection and response of this species are of vital importance. Controlling black locust before a population becomes established will greatly reduce its economic and environmental impacts.

Prevention

Some tips for preventing the spread of black locust include:

Plant native species

Whether you’re an arborist, or a property owner planting new trees, avoid planting invasive tree species and consult a native plant guide before planting.

Stay on the trails

If you enjoy hiking, be sure to stay on the trails and keep your pet on the trail too. Seeds of invasive plants such as black locust can hitch a ride on your boots or your pet’s fur.

Clean your boots, gear, and animals

Inspect and remove plant seeds from your boots, clothing, and pets after a hike.

Report sightings of black locust

Learn what black locust looks like so you can keep an eye out for it in hedges, property boundaries, riparian areas, fence lines, and trails. Reporting supports early detection and response and can keep down economic costs and prevent environmental damage. You can report this species to EDDMapS.

Management Options

There are number of management options for black locust, however it is important to note that these will be most effective on smaller populations. For larger/established populations it is important to recognize that control/management will require a large amount of time and resources. Efforts should initially be focused on protecting key locations and trees (those which are economically/socially/ecologically important) as well as preventing the spread.

Below is an overview of possible methods. Please consult the Black Locust BMP for further details.

Mechanical

Caution: Once black locust is established, any attempt at physical control will encourage suckering/colonization, making it extremely difficult and costly to eradicate fully. For this reason, hand pulling, girdling, burning, mowing and cutting (without chemical control) is not recommended!

Pulling and digging may be feasible if a single sapling is present, but care must be taken to ensure the entire root system is removed.

Bulldozing may be a practical consideration on some sites but, because it will remove all species in the area, is therefore not suitable for ecologically sensitive areas.

Biological

Targeted grazing over many years may be effective in controlling the height of black locust, however it is important to use non-sensitive grazers, such as some goat species, to avoid poisoning the animals.

No biological control program has been attempted and there are no known biocontrol agents for black locust.

Chemical

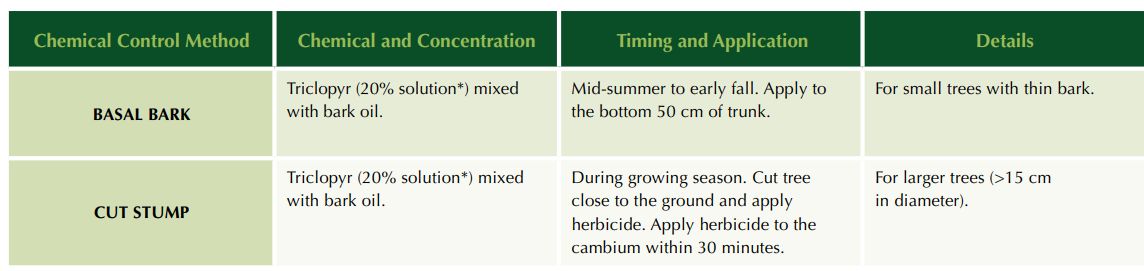

Triclopyr-based herbicides, alone or in combination with other control methods, are the most effective method for black locust control. However, efficiency will depend on the herbicide and concentration used, as well as the timing of the application, and care should be taken to avoid harming non-target plants. Methods include basal bark treatment, cut-stump treatment, drill and fill or injection, and foliar application. See the chart below for more details or refer to the Best Management Practice Technical Document for Land Managers

Caution: Pesticides are not permissible in all circumstances. The Ontario Pesticides Act and Ontario Regulation 63/09 provide natural resources, forestry and agricultural exceptions which may enable chemical control of invasive plants on your property. Other exceptions under the Act include golf courses, and for the promotion of public health and safety. Before applying herbicide, be sure to know the laws and regulations that may apply. For more information on these exceptions and applicable procedures, please refer to the Ontario Invasive Plant Council’s Best Management Practices document for black locust.

Disposal

It’s important to follow proper phytosanitary protocols to ensure this species is not spread through compost or other means.

Viable black locust plant material (seeds and roots) should not be composted but disposed of with regular garbage. Alternatively, solarize viable plant material by placing it in sealed black plastic bags and leaving them in direct sunlight for 1-3 weeks. Alternatively, place in yard waste bags, cover with a dark-coloured tarp and leave in the sun for 1-3 weeks.

Branches and stems that have been cut (and do not contain seed pods) can be burnt as firewood, composted or sent to municipal composting facilities.

Rehabilitation and monitoring

Because black locust is shade-intolerant, re-establishing native tree populations is an important step in preventing reintroduction. Choose native tree, shrub and plant species that can outcompete and shade out new growth.

Soil rehabilitation may also be necessary after black locust invasion due to their ability to fix nitrogen.

Annual monitoring for regrowth is of critical importance to prevent re-establishment of black locust as seeds can remain viable in the soil for decades.

Factsheets

Research

Black locust—Successful invader of a wide range of soil conditions

Vítková et al., 2015. Science of the Total Environment.

Relationships among different environmental variables (physical–chemical soil properties, vegetation characteristics and habitat conditions) were investigated and variables with the highest effect on species composition were detected.

Forest plant diversity is threatened by Robinia pseudoacacia (black-locust) invasion

Benesperi et al., 2012. Biodiversity and Conservation.

Our study confirmed that the replacement of native forests by pure black-locust stands causes both plant richness loss and shifts in species composition. In black-locust stands plant communities are dominated by nitrophilous species and lack many of the oligothrophic and acidophilus species typical of native forests.

Insect invasions track a tree invasion: Global distribution of black locust herbivores

Medzihorský et al., 2023. Journal of Biogeography.

We compiled historical records of the occurrence of insect herbivore species associated with R. pseudoacacia from all world regions. Based on this list, we describe taxonomic patterns and investigate associations between environmental features and numbers of non-native specialist herbivores in the portion of North America invaded by R. pseudoacacia.

Regulation of the growth of sprouting roots of black locust seedlings using root barrier panels

Kitaoka et al., 2022. Journal of Forestry Research.

A method to regulate the development of horizontal roots could be effective in slowing the invasiveness of black locust. In this study, root barrier panels were tested to inhibit the growth of horizontal roots. Since it is labor intensive to observe the growth of roots in the field, it was investigated in a nursery setting. The decrease in secondary flush, an increase in yellowed leaflets, and the height in the seedlings were measured. Installing root barrier panels to a depth of 30 cm effectively inhibit the growth of horizontal roots of young black locust.