Dog-strangling Vine (Cynanchum rossicum)

French common name: Dompte-venin de Russie

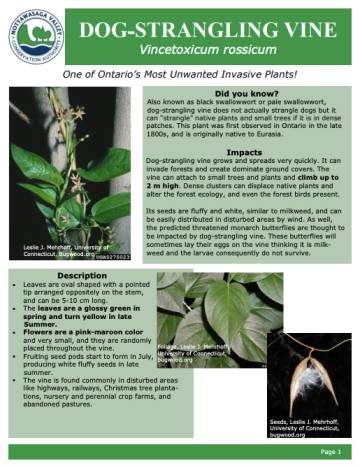

Seedpods of dog-strangling vine typically appear in June and can grow well into the fall.

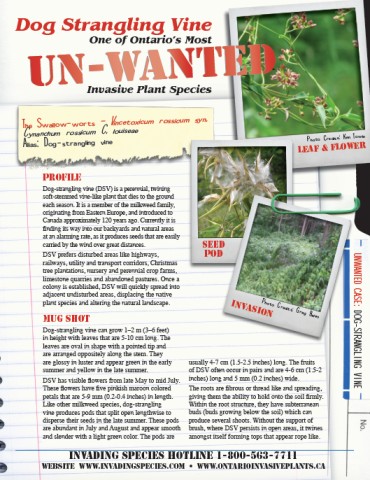

The pink or maroon flowers have five points and are a key identification of dog-strangling vine.

Young plants will grow upright until eventually bending under their weight.

Order: Gentianales

Family: Apocynaceae

Did you know? Dog-strangling vine is a member of the milkweed family.

Dog-strangling vine (DSV), also known as European swallow-wort, is found in parts of Ontario, southern Quebec, and several American states. This plant grows aggressively by wrapping itself around trees and other plants, and can grow up to 2 m high. DSV forms dense stands that overwhelm and crowd out native plants and young trees, preventing forest regeneration. The plant produces bean-shaped seed pods 4-7 cm long and pink to dark purple star-shaped flowers.

Dog-strangling vine is a restricted species under the Ontario Invasive Species Act. It is illegal to import, deposit, release, breed/grow, buy, sell, lease or trade this invasive species in Ontario.

Height: Dog-strangling vine has a woody rootstalk that can grow to 0.6-2 m (24 – 80″).

Stems: Dog-strangling vine has stems that can be somewhat downy (covered in fine hairs) and they can twine or climb. The stems twine around themselves, forming dense mats of vegetation. In the early spring, the stems will grow upright, until eventually bending under their own weight.

Leaves: Leaves are arranged opposite on the stem, smooth, and green with entire to wavy margins. The leaves can vary in colour from dark green to medium-light green; darker green leaves often have lustre. Sizes range from 7-12 cm (3-5″) long and 5-7 cm (2-3″) wide and are oval to oblong, rounded at the base, and pointed at the top. The leaves are rounder and smaller near the base of the plant, largest at the mid-section, and smaller and narrower towards the top of the plant.

Fruit: In late July and August, long, slender, pod-like fruits form at each leaf axil. The pods are 4-7 cm (1.5-3″) long, 0.5 cm (0.2″) wide, and often smooth. Pods contain a milky sap and turn from green to light brown as they grow. The pods split open to release the seeds. Seeds are attached to feathery tufts of hair that aid in their distribution via wind.

Flowers: Dog-strangling vine flowers in late June and July. The flowers emerge at the axils of the leaves in clusters of 5-20 flowers. Flowers have 5 petals and are red-brown or maroon to pinkish in colour.

Dog-strangling vine is found in parts of Ontario, southern Quebec, and several American states. It is very abundant in urban settings throughout southern Ontario. The main known infestations have been found along the southern edge of the province (adjacent to Lakes Erie and Ontario). Another well-established population exists in the Ottawa area. More recently, dog-strangling vine has spread into rural and natural environments. It has also been reported as far north as Temagami.

Impacts to vegetation

Dog-strangling vine can form extensive, monospecific stands that outcompete native plants for space, water, and nutrients. It creates heavy shade and produces chemicals through allelopathy (the release of chemicals from the root of a plant into the soil to discourage other plants from growing nearby) that alter ecosystem structure and function. Dog-strangling vine threatens rare vegetation communities such as alvars, tallgrass prairies, oak savannah, and oak woodlands and their associated species. It can also displace rare and sensitive plant species.

Impacts to wildlife

Dog-strangling vine can negatively affect wildlife by altering habitat. Dense stands have reduced habitat for grassland birds such as savannah sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis), bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus), and eastern meadowlark (Sturnella magna) in New York.

Deer and other browsers avoid dog-strangling vine, which could increase the pressure on native plants that are more palatable. Dog-strangling vine can also affect insects, such as the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), that rely on native milkweed when laying eggs. Butterflies mistakenly lay eggs on dog-strangling vine, instead of their true host plants (native milkweeds), and the monarch larvae then starve because dog-strangling vine does not provide the necessary food source. This could lead to further declines in the population of the monarch, listed as a Species of Special Concern in Ontario and Canada.

Other insect species can also be affected by the presence of this plant, as it doesn’t support many insect groups. It has been observed that both pollinators and plant-eating insects tend to avoid dog-strangling vine, which may also affect populations of birds and small mammals that depend on these insects as a source of food.

Impacts to forestry

Dense patches of dog-strangling vine suppress native tree seedlings, young saplings, and woodland groundcover plants due to heavy shading and can negatively affect forest regeneration. Dog-strangling vine can invade and dominate the understory of mature forests and is of particular concern to woodlot owners.

One of the most pronounced impacts of dog-strangling vine on forests can be found in conifer plantations in southern Ontario. These areas were planted in the early to mid-1900s to control blowing sands and desertification and reduce flooding and erosion. Dog-strangling vine thrives in the filtered light and open soils of some of these mature plantations, suppressing seedling establishment of native hardwoods. If this invasion continues, very few juvenile trees will survive to fill in the shrinking canopy of over-mature pines. Reforestation sites can also be affected, since dog-strangling vine outcompetes planted tree seedlings for sunlight, water, and nutrients.

Dog-strangling vine makes reforestation more expensive. Land managers need to spend more on site preparation, weed control, and often need to buy larger plant material to outcompete dog-strangling vine. It can also reduce plantable space in highly-infested regions, decreasing the potential tree canopy. Dog-strangling vine has also been reported as problematic on Christmas tree farms and nursery operations.

Forestry operations can also be affected by the dense mats formed by dog-strangling vine. These tangles of vegetation can slow down tree marking and walking access which could increase tree marking costs. They would also slow down anyone using a chainsaw in an affected area. However, the biggest challenge for forest managers is the regeneration of the understory (trees and other natural vegetation) on sites with dog-strangling vine.

Impacts to agriculture

Dog-strangling vine is increasingly abundant in agricultural fields and pasture lands across Ontario. Recent observations show that it is moving into corn and soybean fields. There are reports of livestock avoiding this plant and some literature suggests it may be toxic to mammals (e.g. cattle). Heavy growth of dog-strangling vine can short-circuit electric fences around pastures. Livestock can also have difficulty moving through dense mats of the vine.

Impacts to recreation

Dog-strangling vine can inhibit recreational activities in areas where it has become established. The dense tangled mats of vegetation are difficult to walk or bike through, and pets can get tangled in the vines. In the winter, the dead dog-strangling vine stems remain and can hinder skiing and snowshoeing along trails. Dog-strangling vine also reduces the aesthetic value of nature areas by reducing the number and variety of native species.

Mechanical control (eradication)

Digging: Digging is a viable eradication measure for small populations. Land managers have reported that digging up the root crown is more effective than hand pulling and, in some cases, pesticide use. If a newly established plant and its roots are removed, there is a good chance that it can be eradicated. Follow-up is required to make sure seedlings aren’t growing from old seeds and that all plant pieces were removed to prevent resprouting.

Mechanical control (reduced seed production)

Mowing: Dog-strangling vine plants that have been mowed can resprout rapidly and may still produce flowers and seeds. However, properly timed mowing can be an effective way to reduce the amount of seed that is produced, even though it will not eradicate the population. To be most effective, mowing should be done just after the dog-strangling vine flowers and before it produces seed pods. Some land managers choose to mow regularly throughout the growing season to reduce the risk of dog-strangling vine stems tangling in their machinery. Mowing is most effective for monocultures; it is not selective and will impact other species if they are growing in the area that is mowed.

Clipping: For smaller infestations, selective clipping of plants later in the growing season can provide an effective reduction in seed production; however, this method will not eradicate the population. Clipping is considered more ecologically-friendly than mowing, as it is allows for surrounding native vegetation to remain intact. Clipping should be done just after the plants flower and before seed pods are produced.

Pulling: Pulling removes above-ground vegetation and can prevent seeds from forming, however, the stems break easily when pulled, leaving the root crown in place. If the entire root system is not removed, dog-strangling vine can resprout from the root, often more aggressively.

Seed pod removal: For some established populations, land managers have reported that manual removal of seed pods, though time-consuming and intensive, has prevented populations from spreading further. The best time to remove seed pods is just before they start to dry out and split (early to mid-August with follow-up removal until the end of September). This will not eradicate the plant, but will prevent further spread and can be used in combination with mowing for increased effectiveness. Efforts to control spread of the species should focus on areas in which seed pod growth is prolific, such as areas with high sunlight or areas with the densest growth of plants.

Tarping: Tarping refers to covering an invasive plant population with a dark material to block sunlight and “cook” the root system. Tarping is not recommended in low light areas. Tarping is most effective when started in late spring and continued through the growing season and is a viable control method for medium to larger infestations. This method is best for monocultures. To tarp an area, first cut dog-strangling vine stems, taking care not to spread seeds to new areas (this is best done in late spring/early summer before the plant has produced seed). Next, cover the infested area with a dark-coloured tarp or heavy material. Weed barriers used by landscapers or blue poly tarps are good options. Take care to weigh down the tarp material so it doesn’t blow away, but be sure it is still receiving adequate sun exposure. Tent pegs work well as long as the ground isn’t too rocky. The tarp may need to be left in place for more than one growing season to ensure effective control. Monitor for plants growing out from under the edges of the tarp. Replanting the area with native vegetation will help to suppress resprouting and assist in preventing new invaders from establishing. Since tarping essentially “cooks” the soil, mycorrhizae (beneficial soil fungi) may need to be added when replanting.

Disposal

Do not compost dog-strangling vine or use the cut plants as mulch onsite. Dog-strangling vine can leach plant toxins into the soil which are harmful to other species and may reduce the effectiveness of replanting efforts. If plants have seed pods, carefully put all plant material in black plastic bags. Seal the bags tightly and leave them to “cook” in direct sunlight for 1-3 weeks, depending on the temperature and amount of sunlight. If flowers/seed pods have not formed, allow stems and roots to dry out thoroughly before disposing of them. Dispose of all parts of removed plant material, including roots, stems, and leaves to ensure there is no resprouting. Seed pods left on site can ripen, open, and be spread by wind. For large amounts of plant material, contact your local municipality to determine if plant material can be disposed of in the landfill or brought to their composting facility.

Technical Bulletin

In 2017, the Early Detection & Rapid Response Network worked with leading invasive plant control professionals across Ontario to create a series of technical bulletins to help supplement the Ontario Invasive Plant Council’s Best Management Practices series. These brief documents were created to help invasive plant management professionals use the most effective control practices in their effort to control invasive plants in Ontario.

Fact Sheets

These Best Management Practices (BMPs) are designed to provide guidance for managing invasive Dog-strangling vine in Ontario. They were developed by the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC), its partners and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNRF) and Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). These guidelines were created to complement the invasive plant control initiatives of organizations and individuals concerned with the protection of biodiversity, agricultural lands, crops and natural lands

Research

Biocontrol for dog strangling vine (Vincetoxicum rossicum): Longevity and egg maturation of Hypena opulenta (Lepidoptera: Erebidae)

Ontario, and Quebec over the past 40 years. This non-native species from the Ukraine is a

highly competitive species capable of choking out understory plants and trees in Canadian …

Impacts of invasive plant species on soil biodiversity: a case study of dog–strangling vine (Vincetoxicum rossicum) in a Canadian National Park

species, such as dog–strangling vine (DSV)[Vincetoxicum rossicum (Apocynaceae)].

However, in urban ecosystems where DSV invasion is high, there is little research …

Performance of potential European biological control agents of Vincetoxicum spp. with notes on their distribution

(pale swallow‐wort or dog‐strangling vine) grow within forested areas, typically near

rivers (Pobedimova 1952). However, in North America …

Current Research and Knowledge Gaps

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Further Reading

The Invasive Species Centre aims to connect stakeholders. The following information below link to resources that have been created by external organizations.